In the first half of day nine of the teachings on ‘Good Deeds’ by 8th Karmapa, HH 17th Karmapa gave an account of the birth and early life of the 5th Karmapa, Dezhin Shegpa (1384-1415), and explained, in particular, his connection to the Chinese Ming emperor, Yongle.

Today’s post, will focus on the precious objects, which were created and offered to the 5th Karmapa by the Ming Emperor, Yongle, such as a white jade seal and silk paintings and a 600 stanza poem written by the Emperor. This is followed by an overview of the history of Tibetan seals, the scripts used in them and their meaning, with photos and descriptions of other stunning seals given to Tibetan spiritual leaders and rulers by the Chinese centuries ago, and in more recent times.

5th Karmapa’s Visit to China

During the lifetime of the fourth Karmapa, the Chinese Emperor Zhu Yuanzhang (朱元璋), Emperor Taizu of the Ming dynasty (明太祖), who reigned from 1368 to 1398 (Hongwu (洪武) was the title of his reign period) invited the fourth Karmapa to visit him in China. The visit never took place; instead, Rolpe Dorje sent a lama as his emissary.

By examining Karma Kamtsang histories, The 17th Karmapa explained the relationship formed between the Ming Emperor, Yongle (永樂): 1360 – 1424) and the 5th Karmapa. In a Ming Dynasty text entitled the Tales of Four Brothers, when he was young, it says thatYongle heard of a guru Karmapa in central Tibet (U-Tsang) who was unlike any other. Therefore, in the first year of his reign and with his empress’s encouragement, Yongle sent his Inner Minister, the Tibetan eunuch Gonpo Sherab, with a decree inviting the Karmapa to visit the imperial capital, Nangjing, China. In Pawo Tsuklag Trengwa’s Feast for Scholars, Yongle’s decree is recorded to have included these words of invitation:

I heard of your name before when I was in the North and thought I should invite you then. Now that I have ascended to the throne as Emperor, I would like to bring peace to the kingdom and I have been thinking for a long time that we should together bring good fortune to all people…You are inseparable from the Buddha’s intentions, so you should come to China and spread the teachings in order to benefit the kingdom. Also, my mother and father have passed away. I thought I should do something to repay their kindness but have not found a way. As you are skilled in means and activity, please perform rituals to benefit the deceased. Please come quickly.

Five years later, in 1407, the Karmapa arrived in the Chinese capital Nanjing in the twelfth lunar month, when he was 22 years old. The Ming Emperor named the Fifth Karmapa Rúlái Dà Bǎo Fǎwáng, which translated into Tibetan, is Dezhin Shegpa Rinpoche, Chokyi Gyalpo, the name by which the Fifth Karmapa is known today (in English, his name means “Precious King of Dharma”). There are probably over 20,000 words recording the Ming Emperor Yongle and the Fifth Karmapa Dezhin Shegpa’s meeting, which possibly makes it the most written about any Tibetan lama in Chinese historical records.

Against his ministers’ advice, the Ming Emperor Yongle received the Karmapa in-person upon his arrival in Nanjing, with his palms joined and with great respect. Thousands of people and monks gathered to witness the event, elaborate feasts were prepared, and gifts including 10,000 sang of gold, 2000 sang of silver, and ritual items were given in the Huakai Audience Hall.”

Gifts to the 5th Karmapa, Dezhin Shekpa – Monasteries, paintings and jade seal

The Ming Emperor, Yongle offered many beautiful and precious objects to the 5th Karmapa during his visit to Nangjing, and bestowed on him the title of “Master of All the Buddha’s Teachings on Earth With Excellent Prajna Who Has Reached Enlightenment and Is Victorious In the Ten Directions with Perfect Deeds”, ‘ as well as present him with a material representation of the famous black ‘Vajra Crown‘.

Lingu Temple, Nanging and Xiatong Temple, Wutai Mountain

The first example the 17th Karmapa gave of an object offered to the 5th Karmapa was that of the Linggu Temple (灵谷寺;: 靈谷寺; Línggǔ Sì; ‘Spirit Valley Temple’) a famous Buddhist temple in Nanjing[i]: The 17th Karmapa explained that:

“This is where Dezhin Shegpa is reported to have stayed when he was in Nangjing and was offered it, so it became a Karma Kagyu monastery. After that, it was called the Lingu Monastery and there were also some Karma Kagyu monasteries at the Wudang Zhan mountains (where the 5th Karmapa had gone on pilgrimage). These were taken care of by the Great Encampment and recorded in their histories . We can only see the external now, but there used to be a stupa inside. Now, it is like a museum. This is the place where the 5th Karmapa conducted all the grand rituals.”

Later, the Emperor wrote to 5th Karmapa (who was then at Wutai) that he had prayed before the Lingu temple that if his intention was good may another shadow fall from the temple, and it did. then, he did this again, and another shadow came from the temple. For that reason, he said even more devotion and faith arose in him for the 5th Karmapa.

Following in the footsteps of the two previous Karmapas, Dezhin Shekpa also made a pilgrimage to the famous Wu-tai sacred mountains (五台山), to visit monasteries there. Thus, the second example given by 17th Karmapa was the ‘Monastery of Displaying Miracles’ (Xiantong) at the sacred Chinese Buddhist place, Wutai (see image below). The 5th Karmapa stayed here and displayed miracles, and there was talk about this monastery during the time of the 7th Karmapa as well. ”

The 17th Karmapa explained why the 5th Karmapa left Nangjing:

“Wanting to leave behind the hustle and bustle of the capital, on the 13th day of the third month, Dezhin Shegpa travelled to Xiantong Temple on Wutai mountain. In a ‘Supplement to the Lives of the Great Buddhist masters’ it describes the situation at the time:

“The Karmapa was inclined to solitude and didn’t like distractions and so asked the Emperor to be stationed at Wutai. Yet, the Emperor was eager to persuade him to stay and wanted him to stay but after seeing that he was insistent, granted him an imperial carriage to go to Xiantong at Wutai, and ordered the eunuch to renovate the temple where the relics of Ashoka were kept. This monastery was offered to him as his living quarters.””

Chinese paintings of the 5th Karmapa’s Miraculous Displays

Emperor Yongle became an extraordinarily devoted student of the Karmapa, whom he took as his guru. Chinese records speak of the Karmapa’s manifestations, in response to such devotion, as a hundred kinds of miracles. The Emperor recorded these events for posterity in exquisite silk paintings with multi-lingual commentary. The 17th Karmapa explained:

“There is a text called the ‘The Wondrous Decree “Tathagata Precious King of Dharma, Great Maitreya of the West, Peaceful Lord Buddha, and Master of All Buddhist Teachings on Earth”, which is kept in the Library of the Tibetan Autonomous Region, and the paintings in it depict the many amazing events that were recorded when the 5th Karmapa visited Nangjing. In those days (15th Century), one couldn’t take photos or videos so these list what happened from the 5th to the 18th day of the second month. These paintings were written in Tibetan, Chinese and Mongolian, and my Chinese painting tutor and I reproduced them.”

See video here of 17th Karmapa with his painting tutor:

The 17th Karmapa explained that: “When we were copying the paintings and text, we couldn’t find anyone else who could do the other alphabets, so my painting teacher and myself did them only in Tibetan and Chinese. This painting is about 50 meters long and it depicts the events that happened on each of the days.

At that time, it was reported that many wondrous events happened. I wondered about this, was it just a pure vision or something that everyone saw? Later, when we look at Chinese histories these miracles appear to have been seen by everyone. They state that people from Tibet and the western areas said ‘they are showing us illusions and fooling us’. So, they must have seen them.

Many miracles happened, clouds of rains of flowers, and sometimes golden flowers in the city, many clouds of the elders, lights in the sky and so on. It was written down that from the 5th to the 18th days of the month, there were amazing events that everyone saw. They were the 5th Karmapa’s miracles. Some ministers also wrote a poem about these events and later, wrote a melody for it. There was a tradition of singing it in the Emperor’s palace.”

An original of the scroll has been preserved in Tibet. Based on photographs of this scroll, an elderly Taiwanese monk, who tutored the 17th Karmapa in classical Chinese drawing and painting, was able to reproduce the original in collaboration. The 17th Karmapa completed the Tibetan calligraphy on each panel. The reproduction does not include other languages in the original. This recreation of the scroll was then put on display in the 34th Kagyu Monlam Pavilion, but people commented that it was difficult to see the details. So the Karmapa responded by commissioning a high-quality photographic enlargement. It was made in Taiwan and is on display at the Kagyu Monlam in 2017. For more images and information on the 17th Karmapa’s amazing reproductions of these Chinese paintings see here.

Korean envoy – attacks and undermines the Karmapa as a charlatan and ‘meat-eater’

All was not rosy though, as the 17th Karmapa explained:

“The histories also record that an envoy [name is not clear here], came from Korea. The Joeson dynasty (Chosŏn or Chosun, 대조선국; 大朝鮮國, lit. ‘Great Chosun Country’) was no longer under the control of the Ming Dynasty, and so at that point they sent an envoy, to report on the situation and then he would return [it is said that although the Joseon Dynasty considered 1392 as the foundation of the Joseon kingdom, Imperial China did not immediately acknowledge the new government on the Korean peninsula. In 1401, the Ming court recognized Joseon as a tributary state in its sino-centric schema of foreign relations. In 1403, the Yongle Emperor conveyed a patent and a gold seal to Taejong of Joseon, thus confirming his status and that of his dynasty. Between 1392 and 1450, the Joseon court sent 351 missions to China].

The notes the envoy took and their description is called the History of the Dai Country. He says in the text: ‘So, the Dharmic King and monks came from the west and the Emperor paid respects to him as the Living Buddha. He was like an ordinary person who liked to eat lamb meat, but in the nighttime they say he shined like the sun, otherwise he was like an ordinary person.’ He only wrote bad things about the Karmapa. At that time, during its 500-year reign, Joseon encouraged the Confucian ideals and doctrines in Korean society. The first Emperor onwards only respected the Confucian tradition and didn’t pay much attention to Buddhism, and wasn’t allowed to write about Buddhism. So, when their envoy arrived in Nangjing, that is probably why he wrote that the 5th Karmapa eats lamb meat and was fooling everyone.”

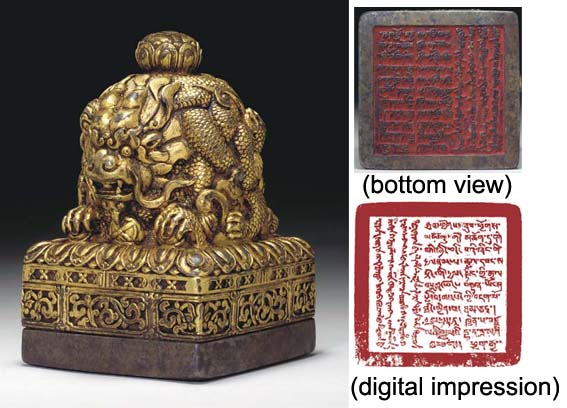

White jade seal given to 5th Karmapa

The 5th Karmapa was also given a beautiful white jade seal by the Ming Emperor. According to the Kagyu Office Taiwan website, the seal script reads: ‘The Ming Emperor’s seal for the Great Dharma King’, (明封大寶法王玉印, Míng fēng dà bǎo fǎwáng yù yìn). The 17th Karmapa described the origin of this particular seal:

“The 5th Karmapa was given a jade seal, which is now in a museum in the Tibetan Autonomous Region. The histories speak about the Emperor’s use of precious materials to craft it. They state that the 5th Karmapa had gone to China and the King has a magnificent piece of jade and wanted to make something with it. Normally, they made seals out of gold and silver, but making them out of jade/jewels was considered even more valuable than that. Some of the King’s ministers advised him that if they gave the 5th Karmapa a jade seal, other will say you are not treating them as well as the 5th Karmapa. So they advised him not to do it. The Chinese emperors used jade seals and so were considered more important than gold. Now, we Tibetans think that gold and silver are more valuable, but this seal is described as such in the Chinese histories. At that time, when they told the Emperor not to give it, he must have given it because now we can see it. The Emperor also gave three Rinpoches the title of Goshri, and among these was the 1st Situ Rinpoche. He was given the name Kenting Naya Tang Nyontse Goshri, Tai Situpa by the Yongle Emperor[ii].”

[According to Tashi Mannox (whom I asked about the seal), “this particular seal appears to be created in Chinese seal script or could be a Mongolian seal script called Tulġur-un üsüg or ebkemel bičig. This is not the more typical Tibetan used Phags-pa based seal script called Horyig”. For more on the script used in the seals, see below.]

History of Chinese seals

“A Chinese seal (印章 yìnzhāng) is a seal or stamp used to mark important documents, pieces of art, contracts, or any other item that requires a signature. The history of Chinese seals can date back to thousands of years ago. Although small in size, the seals symbolize a mysterious culture. In ancient times, the Tibetan ethnic group called the seals “Ji Hun Shi (the stone in which a spirit was reposed)” and handed them down from generation to generation. The seal was said to be first created in 221 BC. After the first emperor of China, Qin Shi Huang, conquered the six Warring States and unified China, he ordered his first imperial seal to be carved using beautiful white jade. The imperial seal was called the “Xi” (/sshee/) and was only used by those in power. The emperors who followed used an imperial seal, but the number of seals changed depending on the dynasty and who was in power.

It wasn’t until the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1912) dynasties that the seal’s usage moved from the imperial to the personal, due to the expansion of the feudal arts. Artists began using a stylized seal carving of their name to mark ownership of their works. Individuals also began using a personalized stamp for important documents. These non-official stamps were called “Yin”.”

Tibetan Seals

In an article by Chinese writer, Yang Guozhen he describes the use of Tibetan seals together with photos of some seals given to well-known Tibetan political and spiritual leaders:

“Possessing great glamour, Tibetan seals are regarded as the gem of China. The textures of ancient Tibetan seals were as follows: gold, silver, jade, cloisonné, rutile, crystal, copper (red copper, brass, white copper and bronze), iron (pig iron, wrought iron and ferroalloy), wood, padauk, sandalwood, red sandal wood, blackwood, box wood and poplar, horny substance (rhinoceros horn, deer horn, ram horn, ivory, ox horn and beast bones) and Dzi bead (Tuo Jia).

Various kinds of scripts were engraved on the seals, including ancient Tibetan, Xang Xung, Tangut, Tibetan, Pagba, Mongol, Chinese, Sanskrit, Nepali, Hui, Manchu and English scripts.

The patterns engraved on the seals were as follows: Ba Rui Xiang (astamangala), Qi Zheng Bao (cakravartin’s seven treasures), Xian Lin Fa Lun (Dharmacakra and a pair of unicorns), Liu Zhong Chang Shou (six kinds of longevity), Wu Miao Yu (five subtle desires), He Qi Si Rui (four harmonious friends), Ru Yi Tou (scepter border’s end), Tian Guan (celestial crown), Tu Ao Fo Xing (convex-concave Buddha’s star), Tai Ji Tu (Diagram of the Supreme Ultimate), Jin Gang (vajra), Pen Yan Mo Ni (flame and treasure symbolizing good luck), Jin Gang Qiao (metallic bridge), 卐-shaped pattern, the Chinese character Shou (which means longevity), the Great Wall, fret, the sun and the moon, Lucky Cloud, Shou Mian Guai Zi Wen (winding beast-head pattern), Hua Cao Guai Zi Wen (winding flower-and-plant pattern), Hua Gai Wen (canopy pattern) and Chuang Wen (pattern of a Buddhist pillar).

The shapes of seal handles are as follows: Bao Zhu, Ru Yi, Tong Ren Guan (peaked hat worn by Lama), Ru Yi Bao Guan, cube, cylinder, tile, elliptic cylinder, lion, frog, tower, bird, bridge, lotus, interlocking lotus, Macaca cyclopis, ox, horse, horse head, tiger and pillar.”

Examples of Historical and Contemporary Tibetan seals awarded by Chinese

Below are some images of seals (from the Guozhen article) and some others that are publicly available online:

According to Guozhen: “The art of seal-engraving in Tibetan areas was quite different from that in Mainland China. By using unique materials and elaborate craftsmanship, ancient Tibetan engravers managed to endow the seals with distinctive decorative effects. Inlaid with gold and silver, the seals blended points, lines and planes with gold and silver luster, which was natural, vivid and gorgeous…..Differing from Han seals, some Tibetan seals were gold-gilding works. Inside the cavity of Tibetan seals, there were pills, scriptures, spell books and the remains of Buddha’s bones, which possessed Jia Chi Li (Buddha’s blessing).”

Seal Scripts

Guozhen says that:

“Various kinds of scripts were engraved on the seals, including ancient Tibetan, Xang Xung, Tangut, Tibetan, Phagba, Mongol, Chinese, Sanskrit, Nepali, Hui, Manchu and English scripts.”

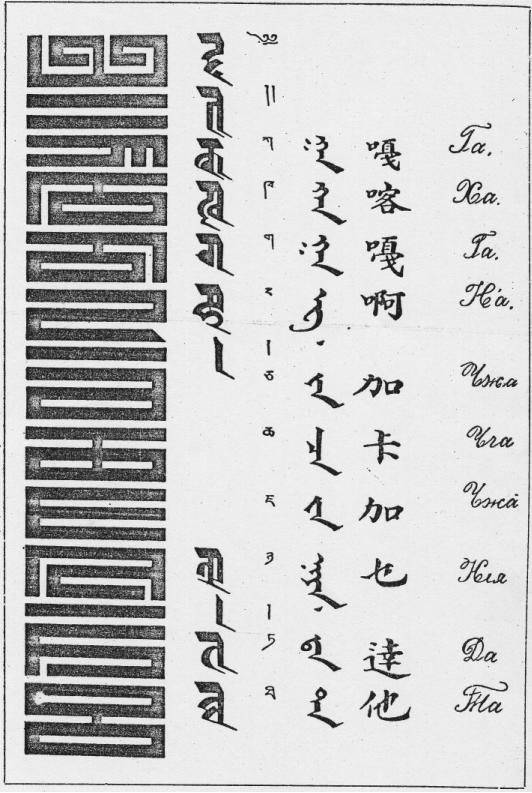

According to a contemporary expert of seals, Tashi Mannox,the most prevalent form of sealscript was that of the Phags – pa (or Hor-yig):

“The special Seal script called Phags-pa or horyig in Tibetan, was created at the time of the great Mongolian Emperor Kublai Khan, who ruled during the 13th century, over China, Mongolia, Tibet, to the North into Russia and south to the borders of Burma and Vietnam. The Emperor seeing a uniformed script was needed across his vast kingdom, issued the standardisation of this script by the learned Phagpa Lodro Gyalsten, who in 1268 devised the namely Phags-pa script. The use of Phags-pa was short lived as a universal written language, however its use lived on as a popular seal script in Tibet called horyig ཧོར་ཡིག this was developed as a ‘modern’ seal script style, which is not only easily translated from Tibetan, but also mimics the labyrinthine geomantic structure of popular Chinese seal script ideographs.

See: PHAGSPA LAMA (asianart.com)

This seal script, which reads vertically, has a strong, commanding visual impression, which was not only traditionally used for official seals but as popular personal seals too. The distinct design of hor-yig was widely used in historical Tibet. For an excellent resource on the script, see here: https://www.babelstone.co.uk/Phags-pa/Description.html.”

The 41 Basic Letters

“The biography of the ‘Phags-pa lama in the History of the Yuan Dynasty (compiled 1369-1370) states that the ‘Phags-pa script comprises 41 letters, but unfortunately does not go into any further detail. However there are two contemporary Chinese works that do enumerate these forty-one ‘Phags-pa letters :

- Fǎshū Kǎo 法書考 : a work on calligraphy composed by the Yuan dynasty Uighur official Sheng Ximing 盛熙明, first published in 1334.

- Shūshǐ Huìyào 書史會要 : a work on the history of calligraphy by the late Yuan / early Ming author Tao Zongyi 陶宗儀, first published in 1376, eight years after the fall of the Yuan dynasty.

The descriptions of the ‘Phags-pa script given in these two works are translated and discussed in my Forty-One Letters page, and are summarised in Table 1. The order of the letters in the table follows the order given in Fashu Kao and Shushi Huiyao.” (Source: https://www.babelstone.co.uk/Phags-pa/Description.html.).

Chinese seal script

“Seal script (篆書; zhuànshū) is an ancient style of writing Chinese characters that was common throughout the latter half of the 1st millennium BC. It evolved organically out of the Zhou dynasty bronze script. The Qin variant of seal script eventually became the standard, and was adopted as the formal script for all of China during the Qin dynasty. It was still widely used for decorative engraving and seals (name chops, or signets) in the Han dynasty. The literal translation of the Chinese name for seal script, 篆書 (zhuànshū), is decorative engraving script, a name coined during the Han dynasty, which reflects the then-reduced role of the script for the writing of ceremonial inscriptions.”

Seal Creation – A Dying Art

According to Mannox, very few people can translate these scripts, or create the hand-carved seals themselves called ‘chops’.

“The art of seal design using the horyig seal script is almost non-existent, less so are those who are skilled in hand-carving seals, called ‘chop’ in Chinese, which as an art form, has almost vanished across the far-East. There are perhaps only a handful of people in the world today who know the horyig seal script well enough to translate, let alone create and provide an attractive looking seal design, however none are known to carve the actual chop seals.”

However, modern technology may be the answer, Tashi Mannox creates bespoke seals on demand via his website and another Tibetan, Tashi Tsering, has created an application that allows people to use the Hor-yig script to create their own personal seals, see here.:

“To Tashi Tsering’s surprise, the Horyig font previously reserved for the seals of imperial families and prestigious living Buddhas was particularly welcomed by users. It allows a publishing house to test a vertical layout for the first time and gives Tibetans a chance to have their own seals. “Horyig fonts are not easy to recognize and are barely used now. Growing interest might revive the use of the dying font,” he said.”

Written and compiled by Adele Tomlin, 1st March 2021.

Further Reading

The Chinese and the Karmapas: Historical survey from the 2nd to 19th Karmapas (2020)

The Kangyur and the Karmapas’ role in their publication and preservation (2020)

Seals granted to Tibetans by Chinese central government in history

Ancient Tibetan Seals – chinaculture.org

https://www.babelstone.co.uk/Phags-pa

Examples of Tibetan Seals, E. H. Walsh, The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland(Jan., 1915), pp. 1-15 (16 pages). Published by: Cambridge University Press.

A Comprehensive Handbook of Chinese Archaic Jades: Authentication, Appreciation & Appraisal by Prof. Mitchell Chen, see here: a-comprehensive-handbook-of-chinese-archaic-jades.pdf (exoticjades.com)

A Tibetan Official Seal of Pho lha nas, Wolfgang Bertsch, The Tibet Journal, Vol. 29, No. 1 (Spring 2004), pp. 3-8 (6 pages). Library of Tibetan Works and Archives.

ENDNOTES

[i] The first emperor of the Ming dynasty, Zhu Yuanzhang (the Hongwu Emperor), who overthrew the Yuan dynasty, renamed the city Yingtian (應天), rebuilt it, and made it the dynastic capital in 1368. He constructed a 48 km (30 mi) long city wall around Yingtian, as well as a new Ming Palace complex, and government halls.

It is believed that Nanjing was the largest city in the world from 1358 to 1425 with a population of 487,000 in 1400. In 1421, the Yongle Emperor relocated the capital to Beijing. The city began to be called the ‘southern capital’ – Nanjing (南京), in comparison to the capital in the north.

[i] “Chokyi Gyaltsen (1377-1448) was the first Tibetan incarnation conferred the honorific title “Kenting Naya Tang Nyontse Geshetse Tai Situpa” by the Chinese Emperor Tai Ming Chen (Yongle) in 1407. The title, in shorter form “Kenting Tai Situpa”; or “Tai Situ”, means “far reaching, unshakable, great master, holder of the command”, the Emperor also conferred on Kenting Tai Situpa the titles “The Empowerment Master with Perfection, Magic, Subtle and Compassion”.”