According to the Tibetan calendar, the eighth day of the ninth month today marks the 39th Parinirvana Anniversary of HH 16th Karmapa Rangjung Rigpe Dorje. Yesterday, the official FB page of the Gyalwang Karmapa in the Tibetan language, Layjang, released a photo of 16th Karmapa, with some Tibetan from a teaching the 17th Karmapa gave in February 2016 regarding the 16th Karmapa’s prior activities in the printing and distribution of the Collection of the Translated Words of the Buddha (known in Tibetan as the Kangyur[i]). These words were spoken by 17th Karmapa as part of an event that launched a new digital edition of the Litang Kangyur (more on that below). The photo published states that:

“During the ten years of the Cultural Revolution, Tibet’s political situation underwent tremendous change, and Tibet also experienced great destruction of its cultural resources and religious texts. The 16th Karmapa Rigpe Dorje had the vast aspiration and deep resolve to restore the teachings of the Buddha from their foundation. His extraordinary activity made it possible to print 500 copies of the vermillion Dege Kangyur in Delhi from 1976 to 1979, and further, he opened wide the gates of generosity and distributed the Kangyur to the monasteries and libraries of all Buddhist traditions without the slightest bias. At end of 1981, the 16th Karmapa also began the reprinting of the Tengyur, which was continued and completed by his General Secretary Damcho Yongdu.”

Inspired by this post, and as a commemoration of that activity, here is a short post about the Kangyur editions and the important role the Karmapas (and Zharmapas) played in their publication and preservation in Tibet.

Yongle Kangyur (1410) – first Tibetan edition of the Kangyur

The Tibetan term, Kangyur (bka’ ‘gyur) means ‘Translated Words of the Buddha’ and is said to be the collection of teachings the Buddha gave himself. When the term Kangyur was first used is not known. There are said to have been altogether thirteen editions of Tibetan Kangyur . Now it is said only eight editions (of Derge, Yongle, Litang, Beijing, Nartang, Jone, Kure and Lhasa) exist. As Nourse (2014) explains, Chinese dynasty emperors and political leaders also played a crucial role in the publication of the Buddhist Canon of texts:

“In the early transmission of Buddhism to Tibet, the translation of Buddhist scriptures

from other Asian languages and their cataloging was largely controlled by the Tibetan emperors. Later, in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, efforts at cataloguing this scriptural corpus and physically producing the first canons were accomplished with wealth that flowed from the powerful Mongol empire. In Tibet, as elsewhere, the production of scriptures, especially large collections such as religious canons, was often accomplished through the patronage of political leaders. This relationship between patronage and sacred book production continued up through the eighteenth century, when we have well-documented efforts at the creation of printed canons sponsored by Asian kings and emperors.” (pp.19-20).

The Karmapas have also played a key role in publishing and preserving editions of the Kangyur. In 2016, 17th Karmapa explained that:

“In general, the words of the Buddha (Kangyur) and the translated treatises (Tengyur) spread widely in the areas of Tibetan culture, and this is due to the special activities of the Karmapas and the Shamar Rinpoches. For example, in the entire world, the first Tibetan edition of the words of the Buddha was produced during the time of the Ming Emperor Yongle (1360–1424) so it is known as the Yongle Kangyur.”

Around 1410 the Yongle Emperor made an offering of the first printed copy of his Kangyur around 1410, to a famous pilgrimage site temple, Pusading, at Wutai Shan, which also now houses the only known exemplar of a forty-two volume supplement to the Wanli Kangyur [ii]:

“The Ming Yongle emperor took a great interest in Pusading[iii]. The monastery was the site of Dawenshu-dian (大文殊殿), the first temple to house a copy of the Yongle edition of the Tibetan Buddhist canon or Kangyur (bka’ ‘gyur). Today, Dawenshu-dian is also sometimes referred to just as Pusading or Zhenrong yuan. The Ming Yongle emperor ordered the reconstruction of Dawenshu dian and then made an offering to the temple of the first printed copy of his Kangyur edition as soon as it was completed around 1410. There were also two temples on Pusading that housed copies of the Wanli print of the Kangyur, Luohou si bentang (羅喉寺本堂) and the Pule yuan bentang (普樂院本堂). Luohou si now houses the only known exemplar of a forty-two volume supplement to the Wanli Kangyur print, but it is missing two volumes.”

The same blocks served as the basis for the slightly revised reprint of the Wanli emperor in 1606[iv] .

The 17th Karmapa further explained that: “The 5th Karmapa Dezhin Shekpa (1384–1415) had a special connection with this text (Yongle Kangyur) and edited it.” The Ming Emperor Yongle is also said to have given the black crown replica of the dakini hair black crown that Karmapas wear during the black crown ceremony, see here.

In Scholar’s Feast by the 2nd Pawo Rinpoche, it states that:

The fifth Karmapa, Deshin Shegpa (De bzhin gshegs pa, 1384–1415), is invited to the Ming imperial court by the Emperor Yongle. Arriving in 1406 and staying until 1408, he has considerable religious interaction with the emperor, persuading him not to be too harsh on other Buddhist sects. At one meeting, the Karmapa sits to the left of the emperor, in the place of honour, with three monastic dignitaries to his left, the State Preceptor (go’i shri), a learned ritual master (slob dpon) and a great scholar.

The Litang (Jiang) Kangyur edition and the 6th Zharmapa

A positive connection between the Jiang dynasty Kings and the Karmapas had been ongoing since the 15th Century and the time of the 7th and 8th Karmapas. According to 17th Karmapa:

“Generally, the kings of the Jiang dynasty had an excellent Dharma connection with the Gyalwang Karmapas. The fifth king Muk Ching had great faith and devotion for the 7th Karmapa Chodrak Gyatso (1454–1506), and made great offerings to him. The seventh king Muk Ting invited the 8th Karmapa Mikyo Dorje (1507–1554) to Jiang, making offerings to him and showing him great respect. Following the intention of the 8th Karmapa, the king did not wage war against Tibet and also promised to send yearly offerings to Central Tibet.

During the reign of Muk Tsang, the 13th king of the Jiang dynasty, the kingdom had spread widely and was prosperous; from Litang in northern area of Kham to Chamdo in the west, a large sweep of territory came under his power. Further, Mu Zeng was very skilled in grammar and poetry and had a deep appreciation of the Dharma as well. It was during the reign of this highly accomplished king that the Jiang Kangyur was published and then transmitted.

The text also states that the Chinese emperor Ching Ngam Tatsi made offerings to the Tibetan regent. To benefit living beings, the emperor invited the Great Bodhisattva [Gyalwang Karmapa] and, treating him like a chief minister, the emperor called together a meeting of his great ministers. The emperor had the inclination to be satisfied, and without making a great effort, he felt that he had swiftly accomplished a great purpose.”

The Litang Kangyur was published due to the efforts of the 9th Karmapa and his student, 6th ‘Red Hat’ Karmapa, Chokyi Wangchug and the patronage of the Jiang Dynasty King. According to Nourse (2014):

“The only other printed edition of the Kangyur (other than the Yongle edition) produced prior to the late seventeenth century was the Jang Satam, or Litang, Kangyur. The work on this Kangyur was carried out from 1609 to 1614 in the kingdom of Jang Satam (’Jang Sa tham), a Naxi kingdom in the area Lijiang in today’s northwest Yunnan province. The king of Jang Satam, known by the Tibetan name Sönam Rapten (Bsod nams rab brtan, d. 1647), invited the Sixth Zhamar (Zhwa dmar) of the Karma Kagyü school, Chokyi Wangchuk (Chos kyi dbang phyug, 1584-1630)[v], to oversee the project. Chokyi Wangchuk brought with him a copy of a Tselpa Kangyur which had been stored at a place called Chingwa Taktsé (’Phying ba stag rtse) and used this as the base text of his editorial work. This edition then, along with the Yongle Kangyur, falls within the Tselpa line of Kangyurs.

Chökyi Wangchuk wrote a narrative catalogue for the collection[vi]. The blocks of the Jang Satam Kangyur were later removed and placed in a Gelukpa monastery in Litang (Li thang) in Kham during the time of the Fifth Dalai Lama, so that this edition of the Kangyur is often known as the Litang Kangyur.” (p.34).

In Describing the Sources of the Kangyur by the 6th Zharmapa, Chokyi Wangchuk, gives an explanation that the original [handwritten] manuscript that served as a basis for the Jiang Kangyur was “the best among the later editions. It was given its name based on the time period and its owner and known as the Tsalpa Kangyur. The masters and scholars who edited, annotated, and corrected it, included Zhonu Tsul Shakyai Gyaltsen, one or two in the succession of the Gyalwang Karmapas, Thamche Khyenpa Chenga Chokyi Drakpa, and Go Lotsawa. In Tibet these days, it is the peerless jewel.”

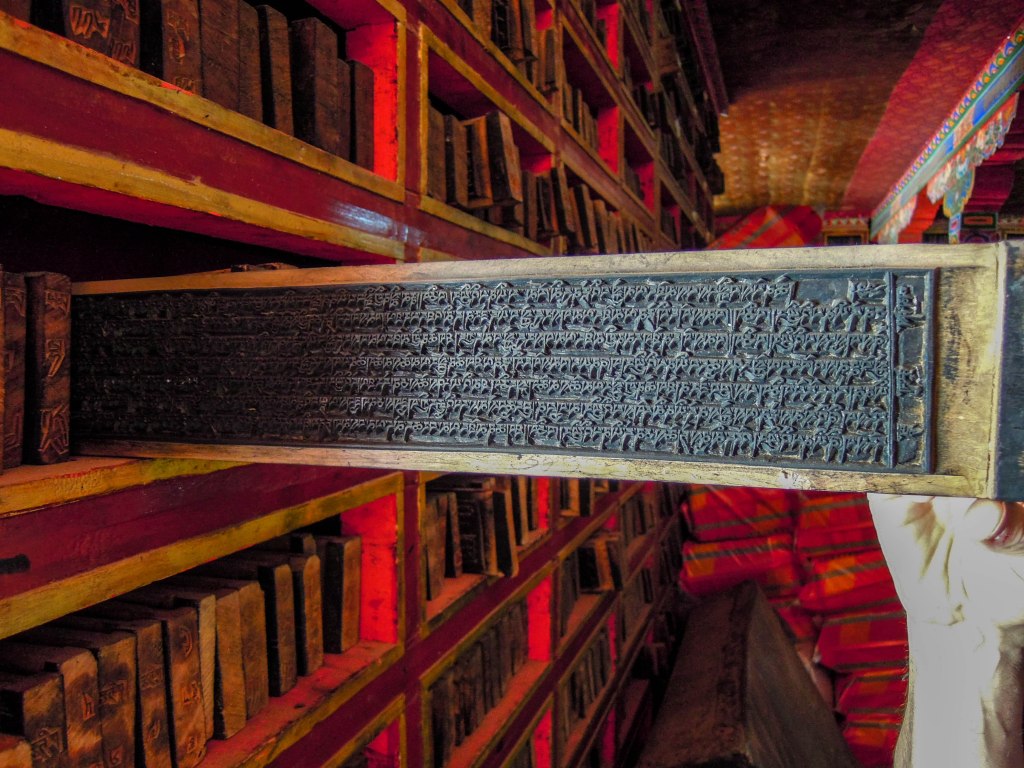

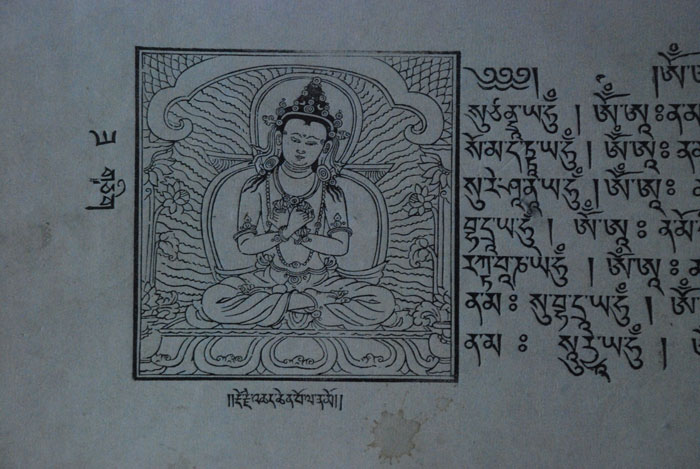

In 1615, the 6th Zharmapa wrote the catalogue (dkar chag) for the Litang Kangyur which is available at TBRC WC1CZ881 ( li thang bka’ ‘gyur dkar chag). It is the original catalogue of the Kangyur carved in Jang Satam. Printing blocks were later moved to Litang. Here is a screenshot I took of the first two folios from it:

The 17th Karmapa explained that “This Litang Kangyur is the very first woodblock edition of the words of the Buddha that was printed in a Tibetan region and so it has an immense historical significance as well as its own inherent value.”

The 17th Karmapa also explained that the Litang Kangyur also became the basis for the Dege Kangyur: “when the great scholar, the all-knowing 8th Tai Situ Chokyi Jungne, was preparing to print the Dege Kangyur (named after the place it was printed), he referred mostly to the Litang Kangyur, though he did change the order and edit it.”[xii]

The Tsalpa Kangyur as basis of the Litang and Derge Kangyurs

The original hand-written manuscript of the Kangyur that the Litang Kangyur was based on, was the only one of its kind in Tibet at that time and considered the best among all manuscripts. Famous as the Tsalpa Kangyur, it was named after its time and its owner[vii]. Nourse (2014) explains its origin:

“The monastery of Tsel Gungtang (’Tshal gung thang) in Central Tibet (Dbus) produced a

number of Kangyur sets under the patronage of the myriarch (khri dpon) Tselpa Künga Dorjé (’Tshal pa Kun dga’ rdo rje, 1309-1364) and his predecessors. An edition of the Kangyur produced between 1347 and 1351 became the basis for many subsequent Kangyur recensions which are thus referred to as members of the Tselpa line of Kangyurs, the other main line in the textual history of the Kangyur (other than Narthang edition). Most of the xylograph editions of the Kangyur are from the Tselpa line. Editions in the Tselpa line of Kangyurs sometimes include a section of ancient

tantras (rnying rgyud) and collected spells (gzungs ’dus) not found in manuscripts of the

Tempangma line (many of the ancient tantras having been excluded by Butön from his

catalogues).”

This Kangyur was edited and annotated by many great scholars, including Zhonu Tsultrim Shakyai Gyaltsen and previous incarnations of the Karmapas and Zhamar Rinpoches, so it was renowned in Tibet as the incomparable Tsalpa Kangyur[viii]. This new printing of the Jiang/Litang Kangyur was based on this Tsalpa manuscript[ix].

The 17th Karmapa described the connection between the Tsalpa Drungchen Monlam Dorje (tshal pa drung chen smon lam rdo rje)[x] and the 3rd Karmapa:

“At the time of the 3rd Karmapa Rangjung Dorje (1284–1339), Tsalpa Drungchen Monlam Dorje had a relationship of priest and patron with the Mongolian Emperor asked him for support [to publish a Tengyur] so the emperor gave to Tsalpa Situ the seal of a Situ and also gifts. Likewise, Tsalpa Situ asked [the 3rd Karmapa Rangjung Dorje] for advice on how to arrange and print the Tengyur. There are the records that can be found. Whether this Tengyur is the Tsalpa Tengyur or the Thukdam Tengyur of the 3rd Karmapa Rangjung Dorje is not very clear. What we know is that there was definitely a relationship between Tsalpa Drungchen Monlam Dorje and the 3rd Karmapa.”[xi]

The Tselpa Kangyur was stored at Taktsé Castle (Stag-rtse), a castle located in the Chingwa (Phying-ba) district of Chonggyä (’Phyongs-rgyas) in central Tibet. According to legend written in the Old Tibetan Chronicle it was home to the kings of Tibet before Songtsen Gampo (604–650) moved his capital to Lhasa. See photo taken below of Chongye by Hugh Richardson in 1949:

17th Karmapa and 2016 digital launch of the Litang Kangyur

In February 2016, the 17th Karmapa launched a new digital edition of the Litang Kangyur, explaining that:

“Eventually, the woodblocks for the Jiang Kangyur were brought to Litang (hence the alternate name) where they remained, but these days only a few of original woodblocks remain. Further, there are just two or three printed copies of the Jiang Kangyur remaining in the world today. So in order to restore and revive the teachings of the Buddha, we have had the meritorious opportunity to use modern technology in preserving the Kangyur, the precious words of the Buddha.”

“This endeavor has been given the name Adarsha, which means “mirror” in English. The reason for the name is that in the future, we would like it to become a program that allows everyone to view and read not just the words of the Buddha, but also of the great Indian scholars of the past and all of the scriptures in Tibetan.

“Adarsha’s home page opens to [a brocade-covered box holding the Karmapa’s edition of the Jiang Kangyur is opened to show] images of the Buddha Shakyamuni in the middle, flanked on the left by the 9th Karmapa, Wangchuk Dorje, and on the right, by the 6th Shamar, Chokyi Wangchuk. If you click on the dark line above the image, three different sections will appear: the Kangyur, the Tengyur, and texts by Tibetan scholars. For the Kangyur tab, all the sections have been input; the Tengyur has just one for now; and the works by Tibetan scholars has just one, but in the future, we hope to include them all.

“There is a regular search engine for the site and also an advanced one, which you can use to search, for example, all the texts that were taught in one place, such as Vulture Peak in Rajgir. It is also possible to search in an easy way more detailed information about a text, such as which turning of the wheel of Dharma it belongs to, the name of the translator, the name of the editor, and other characteristics.

“All of this is available on the website, and for those who do not have Internet access, the program is also available on a USB. Not only will you be able to search the Kangyur on your computer, but also on portable devices, such as iPhones and iPads. The app is now available through the Apple Store. After it is downloaded, the screen looks like this [opening screen displayed]. The internal structure is the same as the website so you can read the entire Kangyur. For example, if you wanted to look at the sutra section, you could browse each of the different volumes, which are labeled with the letters of the Tibetan alphabet, ka, kha, ga, nga, and so forth. The app also has the regular and advance search engines.”

See: https://adarsha.dharma-treasure.org/home/kangyur

The website also includes editions of the Lhasa and Derge Kangyur.

It is inspiring and worthy of great admiration to read about the activities of the Karmapas in the publication and dissemination of the Kangyur (Words of the Buddha) in Tibet and beyond and that this continues up to the present day. May it be of benefit and may the Buddha Dharma flourish!

Written and compiled by Adele Tomlin, 24th October 2020.

Further Reading

- Adarsha: Online editions of Kangyur and Tengyur. See: https://adarsha.dharma-treasure.org

- Paul Harrison, ‘A Brief History of the Tibetan bKa’ ‘gyur’ in Cabezón and Jackson, ed., Tibetan Literature: Studies in Genre, Snow Lion, 1996

- Paul Harrison and Helmut Eimer, “Kanjur and Tanjur Sigla: A Proposal for Standardization,” in Transmission of the Tibetan Canon: Papers Presented at a Panel of the 7th Seminar of the International Association for Tibetan Studies, Graz 1995, edited by Helmut Eimer (Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, 1997).

- James Benjamin Nourse, Canons in Context: A History of the Tibetan Buddhist Canon in the Eighteenth Century, PhD, University of Virginia (2014). See:https://libraetd.lib.virginia.edu/public_view/8623hx969

- Jonathan A. Silk. 1996. Notes on the History of the Yongle Kanjur. In Suhrllekhah: Festgabe für Helmut Eimer. Swisttal-Odendorf: Indica et Tiebtica Verlag.

- Peter Skilling, Translating the Buddha’s Words: Some Notes on the Kanjur Translation Project, Nonthaburi, March 11, 2009

- Peter Skilling, ‘Kanjur Titles and Colophons’ in Tibetan Studies, vol. 2. Oslo, 1994, pp.768-780

- Online searchable Kangyur, provided by University of Vienna

- Translations of the Word of the Buddha at 84000.co

- D. Phillip Stanley (2005) Editions of the Kangyur. THLIB (2005): http://www.thlib.org/encyclopedias/literary/canons/index.php#!essay=/stanley/tibcanons/s/b13

[i] Kangyur (bKa’ ‘gyur) or “Translated Words of Buddha” consists of works in about 108 volumes supposed to have been spoken by the Buddha himself. All texts presumably had a Sanskrit original, although in many cases the Tibetan text was translated from Chinese or other languages.

[ii] https://blogs.cuit.columbia.edu/ajw2203/tag/yongle/. See also Jonathan A. Silk. 1996. Notes on the History of the Yongle Kanjur. In Suhrllekhah: Festgabe für Helmut Eimer. Swisttal-Odendorf: Indica et Tiebtica Verlag.

[iii] According to the same source above: “Pusading 普薩頂/ Zhenrong yuan 真容院 Pusading, a small monastery located on the summit of Lingjiushan or Vulture Peak Mountain, is the highest point in Taihuai, the valley town between the five terraces of Wutai shan. Pusading has been an ongoing center of pilgrimage and imperial sponsorship since at least the Tang dynasty. According to the Expanded Record of the Clear and Cool Mountains (Guang Qingliang zhuan), compiled about 1057-63, the first temple at the site was Wenshuyuan (Cloister of Manjushri), built by Xiaowen (r. 471-499), emperor of the Northern Wei dynasty (385-534). The same record indicates that though apparitions of Manjushri were known to appear on this peak frequently, it was not until the time of the Tang Emperor Ruizong (662-716) that the temple became home to a sculpted image of Manjushri. The tale of this sculpted image gave Pusading its other name, Zhenrong yuan, or Cloister of True Countenance. According to the Expanded Record, the reclusive sculptor Ansheng repeatedly failed in attempts to complete an image of Manjushri without cracks. Finally he appealed to the bodhisattva himself and then succeeded in making a perfect image by modeling it after seventy-two manifestations of Manjushri that accompanied him as he completed his work. Thereafter the monastery was known by the name Zhenrong yuan and was patronized by the emperors of successive dynasties until it was renamed during the Ming Yongle reign period as Pusading, or Bodhisattva Peak, also identified as Manjushri Peak.”

[iv] “The best-known Yongle edition of Kangyur was the cinnabar edition of, based on the Tsalpa edition of and published in Nanjing in the eighth year of the Yongle period of the Ming dynasty (the metal-tiger year of the seventh cycle of Tibetan calendar, 1410) by Ming emperor Yongle. When the block printing of Kangyur was finished, the emperor wrote two eulogies for it: “Eulogy to the Kangyur Published by the Great Ming Emperor” and “Eulogy Granted to the Kangyur by the Great Ming Emperor.” The Chinese originals of the eulogies and their Tibetan translation were printed on the first few pages of the book. At the beginning of each sutra were the following words, “I am grateful to my imperial father and mother who have given birth to me and brought me up, and I seek a way to return their kindness. So I sent people to the western region to take back Tibetan sutras, and had the sutras printed for publication. All living beings in the world will endlessly benefit from it. The merit it brings to us can not be described in words … 1 wrote the preface to praise it in order that it will be passed on forever.” The two eulogies were written on March 9, 1410 (the eighth year of Yongle period of the Ming dynasty).”

[v] https://shamarpa.org/history/the-6th-shamarpa-shamar-mipan-chokyi-wangchuk-1584-1630/

[vi] Nourse (2014) also notes that the 4th Zharmapa wrote a catalogue for the Kangyur (Chos grags ye shes, Zhwa dmar 4 (1453- 1524) Bka’ ’gyur gyi dkar chag bstan pa rgyas byed Kangyur 1519).

[vii] “The Old Narthang (sṇar thang) Kangyur and Tengyur are traditionally viewed as the root source of all subsequent Kangyurs and Tengyurs and Western scholarship held this view until recently. At this point it is apparent that the Kangyur tradition in particular was diverse and fluid. Two main lines of Kangyurs have been identified, the Tshal pa and Them spangs ma lines. Previously, scholars presumed that both of these lines stemmed from the Old Narthang Kangyur but this assumption has been abandoned with mounting evidence that the differences between the two lines make the assumption of a single source untenable. In addition, there are a number of independent Kangyurs that stand aside from the two lines just noted. They often preserve alternate textual traditions and distinctive arrangements of the texts. It has also become clear that over time subsequent copies of these various different Kangyurs began influencing or “contaminating” each other. The resutling picture of the history of the Kangyurs that is emerging is one of complexity and a certain fluidity.” See http://www.thlib.org/encyclopedias/literary/canons/index.php#!essay=/stanley/tibcanons/s/b13

[viii] “Xylograph edition of Kangyur prepared under the Yongle emperor. Dated 1410. 105 + 1 volumes. Begins the Peking sub-line of the Tshal pa Kangyur line and is the first xylograph edition. Two almost complete editions exist in Lhasa. One was known to exist on Wutai-shan in China c. 1940 but its present status is unknown.” See See http://www.thlib.org/encyclopedias/literary/canons/index.php#!essay=/stanley/tibcanons/s/b13.

[ix] “The editorial arrangement of the Litang Kangyur is in accordance with the order of all vehicles, starting with the Four Truths of the first turning of the wheel according to the doctrine of the Buddha, and four Vinaya-sutras. The Litang Kangyur has iocg cases, including 13 cases of Vinaya, 26 cases of Prajnaparamita- sutras, 32 cases of Scriptures of Exoteric School, six cases of Mahavaipulya, six cases of Maharatnakuta- sutra, 24 cases of Tantra, one case of Vimala and one case of catalogue. On the title page of each case are portraits of Seven Buddhas, great Shravakas (personal disciples of the Buddha), the Six Ornaments and Two pupreme Buddhist Philosophers of India, Eight Great Tathagatas, Eight Great Bodhisattvas, Sixteen Arhats, and Seven Protectors of Buddhism. On the title page of the case of Tantra are portraits of the Five Dhyani- Buddhas including Vairochana at the right side, and those of five Dharanis at the left side. This is the first block-printed edition of Kangyur in Tibet.” China Tibetology (Chinese Edition) No. I, 2005

[x] https://www.tbrc.org/#!rid=P9825

[xi] According to James Nourse, in Canons in Context: A History of the Tibetan Buddhist Canon in the Eighteenth Century PhD, University of Virginia (2014). The 3rd Karmapa and Tsalpa Kunga Dorje both produced catalogues of the Tengyur (Rang byung rdo rje, Karma pa 3 (1284- 1339) Rje rang byung rdo rje’i thugs dam bstan ’gyur gyi dkar chag Tengyur ca. 1333- 1336 Rang byung rdo rje Bstan bcos ’gyur ro ’tshal gyi dkar chag Tengyur ca. 1333- 1336 Tshal pa Kun dga’ rdo rje (1309-1364) Bstan ’gyur gyi dkar chag nor bu’i phun

[xii] “The sponsor and patron of the Derge edition of Kangyur was Tenzin Tsering, Derge ‘Iusi of the Kham region. Its collation and printing took five years, from the 7th year of Yongzheng period of the Qing dynasty (the yin-earth-cock year of the 12th cycle of the Tibetan calendar, 1729) to the 11th year of that period (the yin-water-ox year of Tibetan calendar, 1733). The wood blocks of the Derge edition of Kangyur, also called the Derge cinnabar edition of Kangyur, are kept in the sutra-printing house of Derge Gonchen Monastery.

The Derge edition of Kangyur is the source (original) text of all editions of Kangyur printed in Tibet. As for the source text of the Derge edition of Kangyur, according to many Tibetan panditas and sutra-translators, Derge edition of Kangyur was based first on the Tsalpa edition of Kangyur of Chingwa Taktse Castle and the Lijiang edition of Kangyur (or Litang edition of Kangyur) whose original text was the Tsalpa edition. From then on the Kangyur was worshipped in accordance with the vows of Anyan Tenpa.”