“Although Dzogchen and Mahāmudrā are a pair of different names, they are in essence one. “—Karma Pakshi

He asked, “How should one recite it?” whereupon four ḍākinīs sang the tune in unison. The wisdom ḍākinī then said, “If subsequently one uses this tune for the mantra, then all who hear it will be greatly blessed, and it will be of great benefit to beings.”

“His memoir further states that he witnessed infinite peaceful and wrathful deities speaking Buddhist teaching, with multitudes of colors appearing spontaneously. All this was likened to when hail hits a pool of water and bubbles appear immediately yet then disappear, so for him the sensory experiences—due to the subtle energy and mind (lungsem) practices he was engaged in—were not objectified. “

“At that time this yogin said,

“A yogin who realizes the dharmakāya,

Is at all times pure by nature,

He has no fear of the fire and water elements.”

“O, enemies with angry minds,

Now behold this miracle!

Through the subjugation of apparent existence,

I have engaged the cycle of both subtle winds and mind—Wherever

I may go, I will be free of enemies.”

Thus, I said to the aggressive ones.”

—excerpts from ‘The Second Karma Pakshi: Tibetan Mahāsiddha’ (Manson, 2022)

INTRODUCTION

For Ḍākinī Day today, am happy to offer a review of a brand-new new biography of The Second Karmapa, Karma Pakshi: Tibetan Mahāsiddha ((Shambhala Publications) by scholar-translator Charles Manson. I received a brand-new copy of the book to review for a journal (which is much shorter). This article here is a longer essay: a part review of the book and its contents, but also focusing in particular, on one of the fascinating revelations in the book (of which there are many!) about the Second Karmapa’s crucial role in the reception, citation and ḍākinī-bestowed melody of the famed OM MANI PADME HUM mantra, renowned not only in Tibet, but also now globally.

First, I give a brief summary of the significance of the Second Karmapa historically, intellectually and spiritually, together with an outline and overview of the contents of the new book, pulling out some fascinating excerpts along the way. My significantly shorter review of the book (minus images, songs and so on) has now been published by IIAS here.

Second, I consider in more detail, one of the ‘mind-blowingly explosive’ thrills in the book (of which there are many), the teaching of the ḍākinī to Karma Pakshi on the MANI mantra melody. As the 17th Karmapa recently taught himself, the MANI mantra and the Karmapas’ connection with the deity of compassion, Avalokiteshvara, was present long before the mantra ‘Karmapa Khyenno’. To accompany this article, I have recorded the melody and rhythm of the mantra (as decribed in Manson’s book) with visuals here. As you will hear, the tones, melody and rhythm do not follow a straight beat and are slightly dissonant, like a Tibetan singing bowl (which I added in the background). Resulting in some kind of mysterious almost Celtic/John Cage atmosphere to it. Even though it is eight hundred years old, it has a timeless resonance to it. As I recorded the song, it was inspiring and moving to render the melody and rhythm, said to have been taught by the ḍākinī/s. Like being transported back in time with Karma Pakshi’s gorgeous and powerful mind in the room with me. Apologies for the singing/sound quality, it was done on very basic equipment alone.

Manson does not give any information about his own personal connection to the Karmapas in the book, yet he told me when asked that he had first received the Karma Pakshi empowerment from the 16th Karmapa in 1974 and that he started looking at the history of Karma Pakshi (in Tibetan) in 1993, but didn’t really start studying the subject more seriously until 2005. Stating it had been a ‘long, old journey.’

A long journey indeed but well worth it. Before I read Manson’s new book, I had no idea about this ḍākinī teaching on the MANI mantra, so I am grateful for that and many other gems of information about the Second Karmapa’s life and works. In fact, the book was so dense and full of incredible accounts and textual references, that I could hardly contain it within my mind, almost like a mental tremor and explosion of delights! As if Karma Pakshi himself, who speaks about making whole places ‘tremor’ with his breath made my mind tremor with the sheer magnificence and ‘weight’ of the textual and spiritual material packed into the book.

Although the publication would have been ‘enlivened’ with some images/visuals, Manson can be heartily congratulated for writing and publishing this book. It is an excellent and extremely valuable contribution not only to Tibetan Buddhist scholarship, but as a spiritual source of utter inspiration and amazement at what is mentally and physically possible for a great meditation master. As Karma Pakshi writes in his last testament before dying:

“I have not even an atom of fear for death:

Due to being free of any basis for future transmigration and its process,

There will be no transmigration within the dharmakāya—aṃ!”

After reading the chapters on his remarkable life, I could only weep in awe and joy at the passing of this ‘great man’. It would be no exaggeration to say that Karma Pakshi was not only a great man, but also one who saved Tibet from Mongolian invasion and colonisation, who introduced and spread the practice of MANI mantra recitation in Tibet, and who also was the first ‘tulku’ (recognised incarnate of previous master).

In fact, this new book reminded me even more of the heart-breaking situation of the current incarnation of this ‘great man’, the 17th Karmapa, Ogyen Trinley Dorje, who as a young man took the brave (and risky) decision to escape into exile from Tsurphu in Tibet, was never given his own monastery in India during the many years he resided there, and was unable to travel freely until recently. In addition, the divisions within the Karma Kagyu sect (with a rival Karmapa candidate) have only added to the many personal challenges. Thus, it is a ‘living miracle’ that the Karmapa is still with us, alive and teaching and continuing his activities despite it all. Thus, this new book is highly recommended not only inspiring and moving account of an important historical, intellectual and spiritual figure in Tibetan Buddhist history, but also as a reminder of the perhaps unrecognised ‘greatness’ of the present one in our midst.

May the Karmapa’s activities and legacies flourish and survive the samsaric trials and tribulations! May we all study and realise the great compassion and bliss of Red Avalokiteshvara and the four kāyas!

Music? Mani mantra sung in the Karma Pakshi style as taught by the ḍākinī. For the many extraordinary visions, Stevie Wonder’s Visions, and for the sheer inspiration, Amazing by Aerosmith….”Remember the light at the end of the tunnel maybe you….”

Written and compiled by Adele Tomlin, 18th December 2022.

UPDATE January 2023: After publishing this book review and the mantra, Charles Manson, the author, immediately wrote to me saying he loved it and requested permission to use it (and to send him the audio file of it) during his upcoming talks in the USA to promote his book. I sent these to him as requested and happily gave permission.

However, it has since come to my attention, that Manson also used another recording of the melody of the mantra (made after mine) by a white, male medieval music specialist on a European instrument. I do not understand why Manson did this, but all I will say is that to omit the words of the mantra itself, and the female voice, and use a European instrument to play it, seems to me lack the point and blessing of the Tibetan Buddhist mantra given to Karma Pakshi by the dakinis. Manson also publicly cited the prior recording of the mantra Lama Norlha, which I deliberately did not cite due to the proven allegations of sexual misconduct against him by several women.

PART ONE: THE SECOND KARMAPA: LIFE, LEGACY AND WORKS AND NEW BIOGRAPHY

The historical and intellectual significance of the 2nd Karmapa for the Karma Kagyu and Tibetan Buddhism

Considering the great significance of Karma Pakshi, not only for the Karma Kagyu lineage and the Karmapas, but as a remarkable example of a great Tibetan Mahāsiddha (as it states on the title of the book) there is not much research or material on his life in the English language. As Prof. Matthew Kapstein says in his back cover endorsement:

“Karma Pakshi, tantric adept and wonderworker, visionary and emissary to the Mongol Khans, has fascinated and inspired generations of Tibetan Buddhists down to the present day. He remains, however, an enigmatic figure, whose writings and history remain poorly known. Charles E. Manson deserves our gratitude for introducing us to the life and work of an important and unusual master in this attractive, accessible volume.”[i]

In fact, the author of the book, Charles Manson, was one of the few scholars to write about Karma Pakshi, in a Bulletin of Tibetology (2009) article, in which states he will “pay particular attention to the more concrete aspects of his time alive in the human physical form that commonly was associated with the name Karma Pakshi, before presenting, analysing and assessing the spiritual aspects of his life. In short, in current terms, first focusing on the real” putting aside the visionary and esoteric experiences, which he admitted is a ‘large exclusion’.

However, Manson seems to have now addressed that ‘large exclusion’ in this new book, which at almost 300 pages long is reasonably weighty. It is no easy feat to do justice to the life-story and legacy of such a remarkable and powerful person as the Second Karmapa in such a short number of words, yet Manson seems to have pulled this feat off without sacrificing too much accuracy. The content contains many fascinating insights and details into his remarkable life. Although some of the textual sources cited lack page references, it does not detract from the overall quality of the book as a whole[ii].

In terms of historical significance in Tibetan Buddhism, Manson explains, the Second Karmapa was the ‘first’ recognised incarnate (tulku) teacher (2022:31):

“Karma Pakshi was the first to self-identify as Karmapa (he used Karmāpa), and eventually Düsum Khyenpa was attributed retrospectively the epithet of First Karmapa. Thus, Karma Pakshi is often identified, somewhat loosely, as “the first reincarnate,” an emanation of a holy being known as a “trülku” (often commonly rendered as “tulku” from the Tibetan, or “living buddha” in modern parlance).”

Moreover, centuries later, two Buddhist meditation masters, the First Mingyur Rinpoche and Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche, were inspired by Karma Pakshi to write meditation practices that are profoundly important to contemporary Tibetan Buddhist practitioners: respectively, the Karma Pakshi Guru Yoga and the Sādhana of Mahāmudrā. Manson writes:

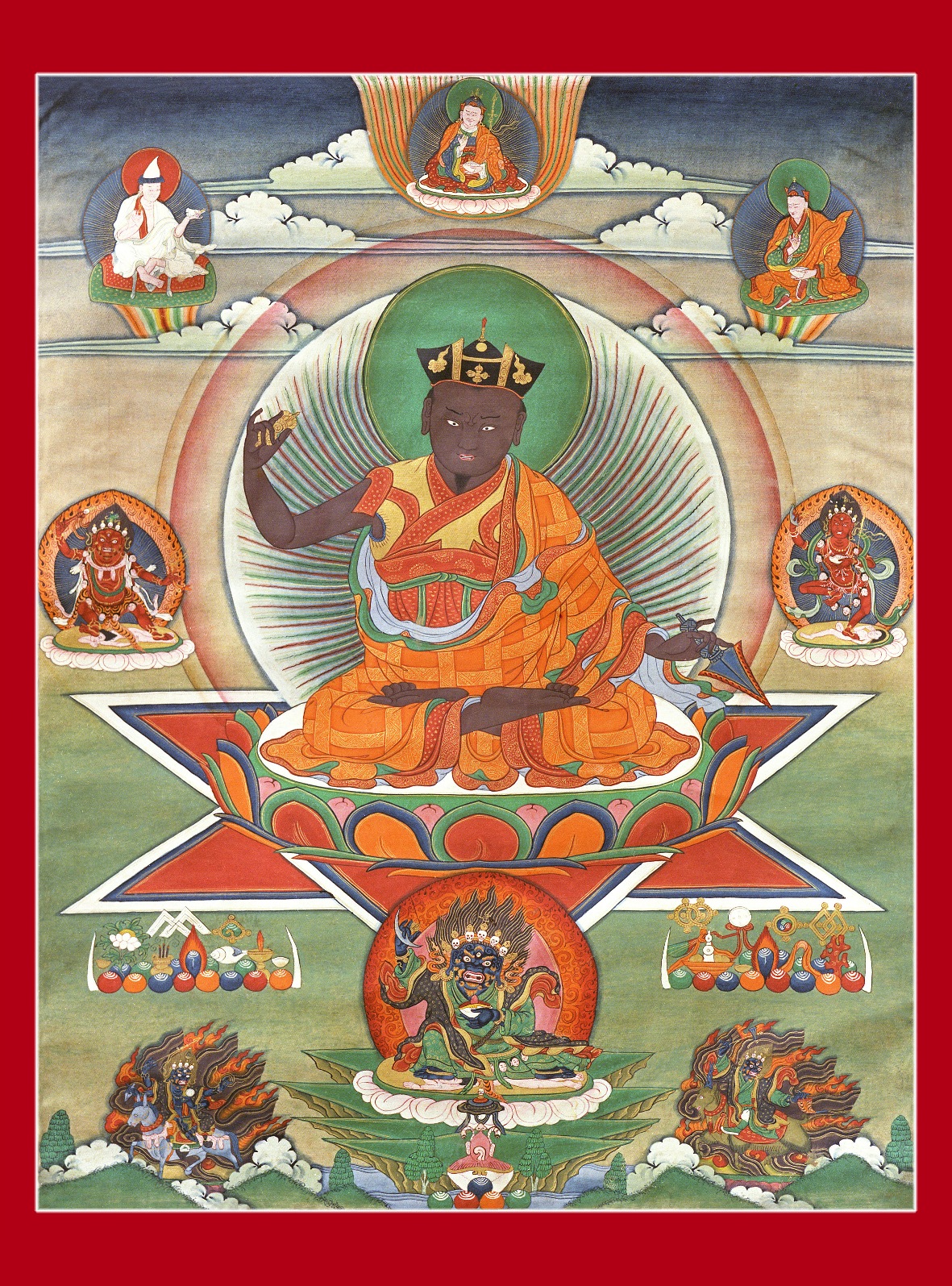

“As a historical figure, Karma Pakshi has been honored in religious artifacts, as can be seen in the numerous scroll paintings (tangkas) and statues of him. He also evokes devotion from Buddhist practitioners of his Kamtsang tradition, as he became the subject of a practice “discovered” in the seventeenth century by the First Yongé Mingyur Dorjé, a contemporary of the Tenth and Eleventh Karmapas. The discovered terma practice is a guru yoga practice derived from Yongé Mingyur Dorjé’s dawn vision of Karma Pakshi giving a short teaching on the nature of mind (from a meditator’s point of view). This visionary inspiration came four hundred years after Karma Pakshi’s death. Mingyur Dorjé’s sādhana praxis is still used almost another four hundred years since its revelation and is of central importance to meditators following the Karmapa tradition.

When the Sixteenth Karmapa made ground-breaking trips to Europe and North America in the 1970s, a primary recommendation he repeatedly made to Westerners was to practice the Karma Pakshi sādhana.

Additionally, in 1968, Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche was inspired in Bhutan by a vision that included Karma Pakshi. Trungpa’s visionary experience became the basis for a practice known in English as The Sādhana of Mahāmudrā, which has become a primary practice for Western followers of Trungpa’s tradition.[iii]”

I recently wrote about a teaching the 17th Karmapa, Ogyen Trinley Dorje gave on Karma Pakshi and also translated some of the guru yoga sadhanas composed for Karma Pakshi by the 3rd and 15th Karmapas, and his connection to the practice of the deity Jinasagara (see here). Karma Pakshi’s self-declared inseparability from the deity Jinasagara/Gyalwa Gyamtso are not mentioned in the book in detail though[iv], although there is reference to it in relation to his receiving the melody of the MANI mantra from the ḍākinī (more on that below).

Textual Sources – Tibetan and English

In terms of the ‘liberation-story’ of the 2nd Karmapa, the only English language biographies available prior to this book were those published on various Karma Kagyu websites, Manson’s 2009 article and Michelle Sorenson’s short (very brief, and at times inaccurate) biography on Treasury of Lives (2011). It would be no exaggeration to say that Manson’s book is the first accurate and detailed account of the Second Karmapa’s life. My review here, which is much longer than Sorenson’s overview, is a ‘middle length’ version of Pakshi’s life (albeit based on Manson’s book).

In that article, Manson helpfully lists the Tibetan textual sources he uses on Karma Pakshi’s life, and these are the same he relies on in this new book too: roughly, Karma Pakshi’s works, a biography by 3rd Karmapa, Rangjung Dorje, the Red Annals by Tselpa Kunga Dorje, and a biography by the 2nd Zhamarpa, Kacho Wangpo (2009:26-27). Here is a helpful table provided by Manson (2009: 50).

THE NEW BOOK: The Life and Legacy of Karma Pakshi

Manson’s book is divided into two main sections, Karma Pakshi’s:

- life and legacy and

- writings

I give an overview (with some quotes) for these sections below.

Early Years: a child prodigy, tantric teacher and studies at Nyingma, Katog Monastery

The first part of the book is a fascinating entry into the life of Karma Pakshi, then known as Chodzin, a child prodigy, who writes in his memoirs that:

“At age six he could read without being taught to do so and at around nine or ten he could read any of the Buddha’s teachings, and just by reading a work just once he would understand and fully assimilate the material.”

Then Manson traces Pakshi’s life as an eleven year-old boy (named Chodzin) meeting the middle-aged tantric yogi, Pomdrakpa Sonam Dorje, (1120-1249) whose visions of the 1st Karmapa, Dusum Khyenpa led him to believe the boy was special and should be his student (2008: 14-15) [v]:

“The master said, “You would be a wonderful student of mine—do not go anywhere, but stay.” Later, that night, during a public religious initiation requested by a Sherap Lodrö, Pomdrakpa had an inspiration. He spoke to Chödzin alone after the gathering had dispersed: “Tonight, directly opposite where you were sitting, Düsum Khyenpa and all the Oral Lineage (Kagyü) appeared clearly. Your karmic tendencies are wonderful.

The teacher then gave instruction on two subjects: “the dohā songs of the Great Brahmin Saraha” and the connascent mahāmudrā meditation instructions of Gampopa (1079–1153), Düsum Khyenpa’s main teacher.”

Manson shares two songs/poems (gur) of Karma Pakshi relevant to these teachings and explains:

“Karma Pakshi’s autobiography remarks that as a result of the instructions received from Pomdrakpa, he came “to know and realize in an instant the infinite wisdom that is self-cognizant of one’s ignorance about all phenomena within samsara and nirvana.”

His memoirs record that he therefore received all the instructions of the lineage, and in particular it mentions the “four points on introduction to the four kāyas.” This instruction later became Karma Pakshi’s preferred teaching to give publicly, which he used during his travels in his middle age, when he taught both Kubilai Khan in China and Möngke Khan in Mongolia.”

Manson explains how Karma Pakshi was heavily influenced by both Nyingma and Sarma traditions, and by the songs of Saraha, saying:

“It is noteworthy that in his memoirs, after quoting a statement attributed to Düsum Khyenpa about the Great Brahmin Saraha, Karma Pakshi remarks that “although Dzogchen and Mahāmudrā are a pair of different names, they are in essence one.” (2022:22)

In the second half of Manson’s book, there are translations of several Karma Pakshi’s writings on the topic of the four kāyas.

Pakshi was then advised by Pomdrakpa to study at Kathog monastery, in Eastern Tibet, whose head was then Tsangton Dorje Gyeltsen (1137-1226) and whose head abbott was Jampa Bum (1179-1252) from whom he received full ordination and got the name Chokyi Lama.

Meditation and visions of deities and mahasiddhas and Pungri hill, near Kampo Nenang

The next chapter considers the yogin life of Karma Pakshi, a rich period of approximately twenty years following his study at Katok, when he developed his deep practices of meditation in remote areas of East Tibet. The place where he stayed the longest, for around eleven years was near the monastery Kampo Nenang (founded by 1st Karmapa, Dusum Khyenpa) at the remote Shar Pungri hill. For more on Kampo Nenang and other places founded by Dusum Khyenpa, see here .

Most of the information in this section is said to be taken from an 18th Century account by Situ Panchen called A Rosary of Crystal Jewels, the Red Annals and the more extensive biography written before 1405 by Kacho Wangpo, the Second Zhamarpa. This is the period where he becomes a noted yogin, attracts hundreds of students and develops a notable reputation. It was this reputation that brings him to the attention of Kubilai Kahn, the warrior prince, who later tried to have him killed several times.

This chapter of Second Karmapa’s visions and meditation experiences is a treasure trove indeed, and one that deserves further delving into in the future. For example:

“..at some point Karma Pakshi had a realization relating to the true nature of phenomena, which he expressed using the simile that “everything appears like an image in a mirror.” His memoir further states that he witnessed infinite peaceful and wrathful deities speaking Buddhist teaching, with multitudes of colors appearing spontaneously. All this was likened to when hail hits a pool of water and bubbles appear immediately yet then disappear, so for him the sensory experiences—due to the subtle energy and mind (lungsem) practices he was engaged in—were not objectified.

For this period of Karma Pakshi’s life, other accounts have embellished the tale with further detail and comments. For example, when Karma Pakshi was practicing the breathing exercises and meditation connected with the “warmth” (tummo) practice, he was able to spend time outdoors in the dead of winter, naked except for a single cotton cloth. In interludes between these meditation sessions, he would often see “Jetsunma,” a reference to Vajrayoginī, an important female meditation deity for the Kagyü tradition used in the visualizations for the practices concerned with the inner subtle energies and one’s mind.

Also, several later accounts state that Karma Pakshi had visions of Buddhist heavenly pure lands with accompanying female spirits or ḍākinīs. At one time, for an entire day, he experienced a vision of a mandala of the fierce dharma-protectors creating thunderous sounds of hūṃ and issuing a prediction to Karma Pakshi that he would achieve extraordinary far-reaching spiritual activity.” (2022:26)

In total, over thirty accounts of visions of deities or siddhas, are accounted for during his stay at Tsurphu and in Central Tibet.

“The Teacher of/from Karma” – Teaching, Travelling and Building and the name Karmapa and Karma Pakshi

The next chapter in the first half of the book, Teaching Travelling and Building, is where Pakshi “developed as a Buddhist missionary, a spiritual adviser to the emperor of the greatest land empire in world history, and as a healer and a peacemaker across Tibet, China, and Mongolia.

The chapter starts with a detailed discussion of how Karma Pakshi got the name Karmapa and Karma Pakshi. On the one hand:

“When the Karmapa epithet first occurred is not stated in the early records. At the time when Pomdrakpa first identifies the boy Chödzin, the eleven-year- old Karma Pakshi, to be associated with Düsum Khyenpa, it is not reported in Karma Pakshi’s memoirs that Pomdrakpa uses the term Karmapa. Rather, the connection to Düsum Khyenpa comes through Pomdrakpa describing his visions to the boy, when he refers to Chödzin as “someone having karmic propensity” (las ’phro). Whenever there is reference to Karmapa in the memoirs, the spelling is usually given as karmā pa, and mostly with the qualifier “well-renowned name.” In most instances in the subsequent Tibetan histories the title is given as karma pa.” (2022:44)

Another possibility, is he got it from the important Karma Monastery, north of Chamdo, founded in 1185 by Dusum Khyenpa, and repaired and enhanced by Karma Pakshi a century later in the mid-1240s.

Regarding the name Karma Pakshi, although Sorensen (2011) matter-of-factly states that he got it from the Mongolians, Manson explores this question in greater detail, considering two possibilities of how he got it, one from the Drigung Monastery monks, the other from Mongolians:

“Curiously, an account from the fifteenth century—the Dharma History—has it that on his journey to Central Tibet in 1249 Chökyi Lama traveled on the northern route, and when he arrived at Drigung Monastery he gained the name Karma Pakshi… If indeed Chökyi Lama did acquire the name Karma Pakshi at Drigung, it would make sense if this followed his adventures in Mongolia, given that Pakshi is a loanword from the Mongolian for “teacher” or “master.”

…. Or it may be that the epithet was acquired in Mongolia, perhaps at the court of Emperor Möngke, where Karma Pakshi taught and initiated the emperor and several members of the court. Indeed, the title may either refer to “the teacher from Karma,” meaning the monastery location, or, more humorously, as a pun on both the place-name and the Buddhist doctrine on karma, which presumably Chökyi Lama discussed at court during his missionary visits. One could imagine the humor of the Karakorum court or of the Drigung monastics referring to the unusual, magical monk traveled from afar as both “teacher from Karma” and “teacher of karma” in one name.” (2022:46).

Then, after the retreat period ended in East Tibet, using the name Karmapa:

“He was initially involved in repairing and developing the monasteries founded by Düsum Khyenpa, the predecessor retrospectively titled the First Karmapa: Düsum Khyenpa’s own works do not contain the Karmapa epithet. In Karma Pakshi’s memoirs, he refers to himself as Karmapa many times, with variant spellings, and less frequently as Karma Pakshi. Thus, it would appear that Chökyi Lama, to refer to Karma Pakshi’s ordained name, was the first in the lineage to be entitled Karmapa—it is not clear whether this was before or after he became known as Karma Pakshi.” (2022:43)

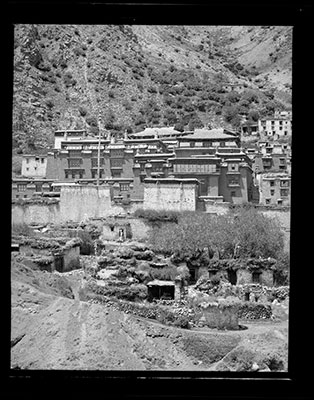

During this period, in 1249, is the time that Karma Pakshi also made his first visit to the now famous Tsurpu Monastery:

“Karma Pakshi wrote little of the six years he spent in Central Tibet based at Tsurpu before he left for China, except to say that he “matured and liberated” people spiritually and made famous the name and teachings of Düsum Khyenpa. His successor the Third Karmapa wrote of numerous visions Karma Pakshi had in the six-year period. In many cases the Third Karmapa gives an interpretation for a vision—for example, a vision in a dream at Tsurpu of “innumerable buddhas” was a sign of Karma Pakshi’s mastery of enlightened activity; a vision of the twelve Tenma goddesses near what is now known as Mount Everest (Qomolangma) was a premonition for Karma Pakshi of conflict and unpleasantness to come, which proved to be the case in his relations with Kubilai Khan.” (2022:50).

Going to Mongolia. miraculous signs and meeting Mongkhe Khan, an incarnation of Dusum Khyenpa’s disciple

The final chapters of this first section of the book, analyse Karma Pakshi’s meeting with the then head of the Mongolian empire, Mongkhe Khan, and his brother the Prince Kubilai Khan, who later arrested him and tried to have him killed several times.

Even en route to meet Mongkhe Khan (at his invitation) in Karakorum (a trip over the Gobi desert of over 1200 miles), Pakshi displayed miraculous signs such as: causing poisonous insects of the area to fall to the ground (2022: 59).

“Interestingly, Pakshi intuits that “there was a significant connection to be made between Möngke Khan and the tale of one of Düsum Khyenpa’s previous lives. Düsum Khyenpa had recounted to his own disciples a typically Buddhist tale that in an earlier life, in the western continent Bountiful Cow, he had been born as an elephant in a royal herd belonging to a malicious infidel king. The elephant had contrived to crush the king to death, in order “to rescue from the lower realms this king who was acting like a despot.” According to several early accounts of Düsum Khyenpa’s remembered previous incarnations, the malevolent king in subsequent lives became a disciple, eventually becoming Düsum Khyenpa’s sponsor, Gönpawa….

As Karma Pakshi journeyed to the capital of the empire, he intuited that the king killed by an elephant had been reborn as Möngke Khan and that because of the emperor’s habits of previous lives he “maintained the tenets” of Christian and Daoist masters.” (2022: 59-60)

On meeting the Emperor Mongkhe Khan he commanded Pakshi saying “I am the ruler of the world – get rid of my obstacles!” With Pakshi bravely replying, “Tonight, I will think about it a bit.”

“According to Karma Pakshi’s memoirs, his demonstration of omens and miraculous visionary manifestations at the royal court was overwhelming, to the point where the royalty present—even the titular heads Möngke and Ariq-Böke— eventually decided to take up the teaching of the Buddha. Consequently, there seems to have been a distribution of goods to all people in the area from the royal treasury—one of the several social-benefit themes of Karma Pakshi’s influence on the emperor—upon which a disembodied voice was heard saying of the emperor, “You are greathearted and generous!” (2022:64-65)

In short, Karma Pakshi’s influence on Mongkhe and his kingdom had a very beneficial effect in terms of Dharma and Buddhist ethics, including several amnesties for political prisoners, and he acclaimed Mongke as a great Dharma King.

Karma Pakshi decided to return to Tibet after having a “vision of Düsum Khyenpa riding a blue lion, traveling in the sky surrounded by siddhas. The Düsum Khyenpa of the vision said to Karma Pakshi that the spread of the Buddhist teaching would decline, and therefore he was requesting Karma Pakshi to return to Tibet. Consequently, Karma Pakshi said to the emperor, “I will not stay. I will go to Tibet—I should accomplish great deeds there.””

Escaping and overcoming Kubilai Khan: tales of torture, assassination attempts, exile and friendship

Manson (2022:79) explains:

“Karma Pakshi does not write on the details of the imperial conflicts, and his information on the personal episodes that he does recount of the period is somewhat sparse. He himself seems to have been busy using the donated wealth for his missionary and reparation projects in the areas of China northeast of Tibet (which he refers to as “borderlands”), either commissioning statues, stupas, and buildings, or even getting manually involved in the projects himself. He saw these religious projects as accomplishing enormous benefit for sentient beings at a time when moral virtue was diminishing. However, Karma Pakshi does record that Kubilai issued a “fierce edict” against him, which may well have been a death warrant.

The reason appears to have been two-fold: a perceived friendship with Kublai’s rival/enemy Ariq-Boke, and the slight of Karma Pakshi leaving Kubilai’s entourage in 1256. Karma Pakshi himself writes that it was the court advisors who has seen ‘the bearded one’ as an evil spirit. Another account in the 16th Century history Feast For Scholars by Pawo Tsuglag Trengwa states it was during an initiation Karma Pakshi had given, in which some of ‘the nobles’ had not received the vase during the empowerment and took offence at it. This resentment then resurfaced years later among the courtiers that led to his arrest after Mongke’s death. (2022: 80-81)

Regarding the capture and torture of Karma Pakshi, his miraculous powers and ability to avoid death deserve a book in their own right. Manson explains (2022: 82-83)

“The capture of Karma Pakshi has several interpretations in the historical accounts, giving the dramatic failures of hundreds of soldiers to capture or kill the miraculous adept, who seems to have been unaffected. The Red Annals—written in 1363 by a retired Tibetan dignitary, Tselpa Künga Dorjé, who had been at a court of the Yuan dynasty, following in the footsteps of his father and grandfather as administrators at court—briefly recounts that the soldiers had tried to burn Karma Pakshi, drown him, throw weapons at him, and poison him, to no avail. Subsequent historians follow much the same account, occasionally adding the additional trial of being thrown off a cliff. The Blue Annals makes the observation that two of Karma Pakshi’s disciples, Yeshé Wangchuk and Rinchen Pel, died from being burned during these trials, but gives no further detail. Karma Pakshi’s account is more visionary, and he accentuates the positivity of his immunity from being harmed and his triumph over adversity….. In the ensuing chaos, people lost their lives, others were struck down by illness, and some were just terrified. Faith in the Buddhist master, who was defying execution, was awakened. Such a miracle, Karma Pakshi wrote, had not been seen or heard of before by anyone.”

This period was then followed by Kubilai mitigating the imperial death sentence to one of exile and then again after two years in exile, meeting (and this time converting) Kubilai Khan:

“After the two years in exile by the lake or sea, Karma Pakshi proceeded to a place he called Chongto, which is likely to have been Zhongdo, the old Jin dynasty capital a little southwest of the site where Dadu was yet to be established. He was probably summoned by Kubilai, who seems to have continued in his mistrust and antagonism toward Karma Pakshi. At this meeting, two years since their catastrophic previous meeting, Kubilai had Karma Pakshi locked up in an “Avalokiteśvara temple,” with the doors nailed shut and three guards in shifts watching over the temple—there was no chance of escape. The imprisoned yogin proceeded to manifest ḍākinīs and deities within the temple. The manifestations could be seen from the outside his prison, as the walls had apparently become transparent.

Such miraculous events seem to have affected the Khan. …. Kubilai had had a significant change of heart. So he set free his prisoner, telling him, “Wherever you wish to go in Tibet, please perform Buddhist prayers for me.” With that, Karma Pakshi set off on the lengthy return to his homeland in East Tibet, and then a farther journey to Tsurpu, which in all took eight years.”

These important details, and records of the incredible feats of meditational power by Karma Pakshi are barely mentioned in Sorensen (2011).

Return to Tsurpu and construction of the sixty-foot Buddha statue ‘Ornament of the World’

Karma Pakshi returned to Tsurpu in the early 1270s, where he proceeded to build The Ornament of the World Great Deity, sixty-foot huge Buddha statue. The statue was completed as being ten ‘arm spans high’ and British Tibetologist, Hugh Richardson (1905-2000) confirmed this was the size of the statue on seeing it in 1948 and 1950. The statue was completely destroyed during the Chinese communist Cultural Revolution (2022:93-5). For more on Richardson’s visit to Tsurpu, see Richardson (1987). Memories of Tshurphu.

Karma Pakshi’s memoirs contain a whole section—eight folios in length—devoted to his observations and thoughts on the Ornament of the World statue, entitled “Biographical Account of Building the Ornament of the World Great Deity.”

“The account briefly alludes to the expense of creating the huge work, funded by the wealth gained in his extensive travels. At some point while building the sculpture, a light shone from the top of the “throne”—probably referring to either the top of the decorative bas-relief often found behind a buddha statue, or to the top of the platform the statue was to be seated on—and there were earth tremors for two days over the whole region. The tremors were interpreted as an omen of the negative forces of demons and heretics instigating obstacles to the artists’ work and causing dissension.” (2022: 97)

For more on the Karmapas and Tsurpu, see INDESTRUCTIBLE MIND MANDALA OF THE KARMAPAS, TSURPHU MONASTERY: Origin, history, rebuilding ‘Praises to Tsurphu’ by 3rd and 16th Karmapas

Passing into nirvana at Tsurpu monastery and miraculous signs and relics

In 1283, when he was seventy-nine years old, Karma Pakshi then passed away at Tsurpu (on the Sheep Year, 3rd day of the 9th month). Manson refers to his last testament and also an account by Situ Panchen where Karma Pakshi spoke some verses on his deathbed before passing:

“He asked those present not to touch his body for seven days after death. Several accounts describe the signs that occurred at the time of death or shortly thereafter: two suns appeared in the sky, and there was a “rain of flowers” and unusual sounds. Karma Pakshi’s cremation, at his prior request, took place within ten days after his death—it seems he did not favor embalming. Various relics were found afterward in the cremation ashes: Karma Pakshi’s heart, tongue, and eyes, as well as ringsel relics with markings associated with tantric practices (rare conch shell designs, deity insignia, and seed syllables of meditation deity mantras). The great man had gone.” (2022:109-114)

Richardson (1987) refers to the tomb of Pakshi in his memoir as ‘austere’ and without any elaborate decoration.

Legacies, lineages and the Bernagchen-Rangjung Gyelmo union protectors practice

In the final chapter of the first half of the book, Manson details some of the legacies and lineages of Karma Pakshi. In particular, that of Jināsagara (Red Chenrezig/Gyalwa Gyamtso), Bernagchen/Black-cloaked Mahakala, the now famous protector of Karma Kagyu, the instruction on the four kāyas (about which a lengthy 3-4 volume work was composed 250 years later by the 8th Karmapa), the termas sadhanas of Mingyur Yongey Dorje and Chogyam Trungpa mentioned earlier. Regarding the protectors:

“The main protector practices of the earlier Kagyü lineage holders were not of Bernakchen—it is with Karma Pakshi that the Bernakchen tradition became the main protector associated with the lineage. The Bernakchen lineage is said to have come to Karma Pakshi from his father (from a Nyingma lineage), but this protector lineage is also traced from Drogön Rechen to Pomdrakpa to Karma Pakshi. The tangka depictions of the Bernakchen and Rangjung Gyelmo figures riding a mule together also feature Karma Pakshi in prime position above the deities—it may be that he was responsible for introducing this “brother-sister” practice to the Kamtsang lineage.” (2022: 122)

Songs, Poems and Writings

The second section of the book contains several translated songs, poems and essays by Karma Pakshi. It is clear that Pakshi was a very able poet and gur singer, as evidenced in this clip here in the 17th Karmapa’s play on his life (see photo below).

There is a fascinating section on a text about the previous lives (preincarnations) of Karma Pakshi, from a text that Manson says was provided by the 17th Karmapa, Ogyen Trinley Dorje. Other translated writings include Pakshi’s account of the building of the Great Ornament of the World and his deathbed song. There are also several texts on meditation, in particular, his teaching on the four Kāyas, which he taught in many places. Not easy to understand without the guidance of a realised master though! I cannot do justice to this section of the book in such a short space of time, but will perhaps use some of the material contained in it for future research articles here.

PART II: THE ORIGIN AND MELODY OF THE MANI MANTRA IN TIBET

Mani melody taught by Dakini to Karma Pakshi

Putting aside the content overview of the book, for the second half of this review/essay, I pull out one (of the too many to mention) fascinating and remarkable aspects of Karma Pakshi’s life within it. When a ḍākinī taught Karma Pakshi the melody to chant the famous OM MANI PADME HUM (MANI) mantra.

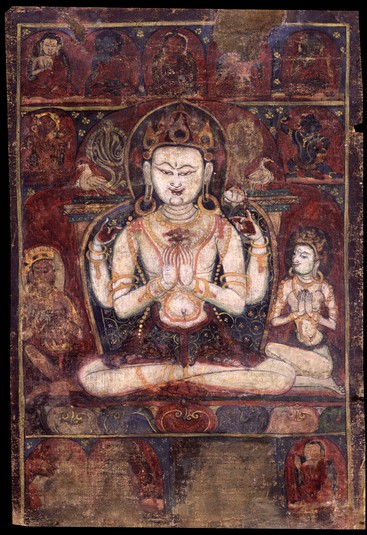

During the Meditation Development in the first half of the book (before he was called Karma Pakshi) Manson mentions Pakshi’s special connection to the Avalokiteśvara practice, and his reports of several visions of this deity associated with compassion practice, in particular the Jinasāgara tantric aspect of Avalokiteśvara[vi]. This is not described in great detail though. For more on the inseparability of Karma Pakshi from Jinasāgara/Avalokiteśvara, and information about the practice, see my recent articles here and here. In addition, it was the deity who warned Pakshi not to stay at the Prince Kubilai Khan’s encampment when he first met him:

“After he had invoked Avalokiteśvara in his Buddhist practice, the deity told him, “Do not

stay here for a long time. I foresee much greed and anger will occur. Go to the wider plains farther north, where you will be respected by everyone.” (2022: 55).

Manson then cites two textual sources that state how the young man received the melody of the MANI mantra from wisdom ḍākinī/s. This was the first I heard of this and was fascinated to read that:

“As a further indication of the link with the deity of compassion, in the Red Annals (completed 1363), the author Tselpa Künga Dorjé wrote that a wisdom ḍākinī taught Karma Pakshi a special tune for singing the famous six-syllable maṇi mantra (oṃ maṇi padme hūṃ) associated with Avalokiteśvara. Tradition has it that Karma Pakshi promulgated the tune, which came to be used widely in communal singing of the mantra.”

Manson then backs this up with a slightly more elaborate account written by the Second Zhamarpa, a generation after the Red Annals, in which:

“An esoteric-wisdom ḍākinī appeared in a dream, surrounded by an ocean of dancing ḍākinīs, and said to Karma Pakshi, “You do not know how to recite the maṇi mantra.” He asked, “How should one recite it?” whereupon four ḍākinīs sang the tune in unison. The wisdom ḍākinī then said, “If subsequently one uses this tune for the mantra, then all who hear it will be greatly blessed, and it will be of great benefit to beings.”

I quickly checked the Red Annals, and this instruction from the ḍākinī was said to have happened before Karma Pakshi became a Getsul/Novice monk.

Furthermore, in a song attributed to Karma Pakshi, named in the colophon as “Melody of Karmāpa’s Intention, he extols five “necessities”, one of which is the MANI mantra and its benefits:

“All buddhas in all times

As miraculously compassionate Avalokiteśvara

With the six-lettered superb speech mantras

Act for the benefit of beings—that is a necessity.”[vii]

However, Manson then explains that the melody that Karma Pakshi would chant the mantra is not the same as the one today, and furthermore has its origins with the dakinis.

“The singing of the maṇi mantra in communal settings is a tradition whose origins have been credited to Karma Pakshi’s vision, but the simplified tune that is currently promulgated widely is apparently not the same as the tune received by Karma Pakshi.

In the twenty-first century the late Lama Norlha—known as a skillful chanter at Pelpung Monastery—at this author’s request did sing the tune in the tradition of Karma Pakshi. From the recording (made in 2006), the contemporary composer Dirk de Klerk notated the tune.”

The recording of Lama Norlha is available online. However, as he is quite a controversial lama when it comes to sexual misconduct towards women (reported by Lion’s Roar here), I have (daringly, or disastrously who knows!) decided to record it myself as a video/visual Youtube track here for those who cannot read musical notation, and who might like to hear it in a female voice (like the ḍākinī!).

I have lowered the pitch of the notes for my voice, but the melody and timing remains the same. As you will hear, the tones, melody and rhythm do not follow a straight beat and are slightly dissonant, like a Tibetan singing bowl (which I added in the background). Resulting in some kind of mysterious almost Celtic/John Cage atmosphere to it. Even though it is eight hundred years old, it has a timeless resonance to it. As I recorded the song, it was inspiring and moving to render the melody and rhythm, said to have been taught by the ḍākinī/s. Like being transported back in time with Karma Pakshi’s gorgeous and powerful mind in the room with me.

17th Karmapa on 2nd Karmapa’s connection to the MANI mantra

In 2012, the 17th Karmapa composed and directed a three-part play about the life of Karma Pakshi. which can be watched on Youtube here: Karma Pakshi and a Jataka tale : A play with dance and a Tibetan opera – Tibetan Language Only.

Recently, the 17th Karmapa (February 2021), in an online teaching (which I wrote up in detail here[viii]), spoke about the deep connection between the MANI mantra and its melody and the 2nd Karmapa and subsequent Karmapas (in particular the 5th Karmapa). He explained that:

“The reason to recite the Mani mantra and use the prayer wheel is said to have come from the time of the Karma Pakshi. The main reason for this is because his main yidam was Red Chenrezig, Gyalwa Gyatso, and he had a vision. In that vision the dakinis of the five families told him he should get large gathering of the public and recite the mani mantras with the melody the public, and everyone who sees and hears it would be blessed. So Karma Pakshi had this vision and would wear the black crown and sing the mantra with the melodies. This is described in many Dharma histories, particularly the Feast for Scholars. In more recent histories, when Drogon Chophag [5th Sakya Trizin, 1235-1280] went to Mongolia, some people would say ‘Oh Karma Pakshi is nothing but a Mani reciter’. The Hor Emperors really respected Drogon Chophag but not Karma Pakshi. However, the point is that the tradition of reciting mantra and mani prayer wheels in Tibet is because Karma Pakshi spread them. As the 7th Panchen Tenpai Nyitsten, and other scholars and masters have also said.”

Then in another teaching on the 5th Karmapa (March 2021), the 17th Karmapa continued that:

“Thus, at the time of the earlier Karmapas, people were primarily benefitted by the mani mantra and the mani melody, as that was the melody sung at that time. When 5th Karmapa, Dezhin Shegpa performed the ceremonies and rituals, and every day so many auspicious signs occurred, that people of all ranks, ordinary people also naturally developed faith and belief, and would recite the mani mantras, day and night.”

What is the relationship between having faith in the Karmapa and reciting the six-syllable mani mantra? Isn’t that the mantra of Avalokiteshvara? In this text there are 126 Buddhas and Bodhisattvas and the 26th is the 5th Karmapa. In the Chinese it clearly reads: “The mantra of Guru Karmapa, the Precious King of Dharma, OM MANI PADME HUM”. The Tibetan text is not so clear and reads: “I prostrate to the Lord of Dharma, Karmapa, OM MANI PADME HUM.” At that time, he explained, there was no tradition of chanting “Karmapa Khyenno.” As we do these days. Because the Karmapa was considered an emanation of Avalokiteshvara, there was the tradition of reciting OM MANI PADME HUM, the mantra of Avalokiteshvara. What is more, Karma Pakshi had emphasized the mani practice so much, and when Dezhin Shegpa went to China, he also recited it as well. Thus, the six-syllable mantra also spread widely in China under the influence of the Yongle emperor There seems to be a profound connection here[ix].”

Since the Karmapa is considered an emanation of Avalokiteshvara, the Karmapa explained, it is not surprising to find the six-syllable mantra associated with him. There was also a tradition of people (known as maniwa, the mani people) putting the mantra to a melody and singing it to benefit others as they traveled around Tibet. This custom dates from the time of the Second Karmapa, as does the tradition of mani wheels. This is confirmed, the Karmapa stated, in a history by the sixth or seventh Panchen Lama, in which he discussed the benefits of mani wheels and traced them back to Karma Pakshi. So, there is a special connection between the Karmapas and the six-syllable mantra. The 17th Karmapa also described how the 5th Karmapa was pictured in an old Chinese text with the MANI mantra written below him[x].

Conclusion

As I stated in the Introduction, this new book on Karma Pakshi is an excellent, vivid valuable contribution to the research and translations of one of the most important historical and spiritual figures in Tibetan Buddhism, in particular that of the Karmapas and Karma Kagyu. The lives of the various Karmapas are inspiring indeed and I hope that in the future, Shambhala will publish similar books on the other Karmapas, such as the 5th and 8th.

Nonetheless, as I said in the Introduction, Manson’s monograph is even more than a fascinating historical or intellectual memoir, it is a spiritual revelation leading the reader to only gasp in awe and imagine what such a powerful, spiritual yogic practitioner was able to do mentally and physically. On first reading some of the book, I lay down on my bed, with tears rolling down my face, thinking and dreaming, “Imagine meeting, or knowing someone like that……amazing. Just amazing!”

Bibliography

English-language sources

Karmapa, 17, Ogyen Trinley Dorje. (2015). Teaching and empowerment of Karma Pakshi in the USA.

Manson, Charles. (2009). “Introduction to the Life of Karma Pakshi (1204/6-1283). Bulletin of Tibetology 45, no. 1, pp. 25-52.

Manson, Charles. (2022). The Second Karmapa, Karma Pakshi: Tibetan Mahāsiddha. Shambhala Publications.

Mani mantra – Karma Pakshi tradition – Lama Norlha recording 2006 by yeshiuk (soundcloud.com)

Richardson, Hugh. E. (1987). Memories of Tshurphu. The Tibet Journal, 12(1), 36–38.

Sorensen, Michelle. 2011. “The Second Karmapa, Karma Pakshi,” Treasury of Lives.

Tomlin, Adele (2021 and 2022):

(2022). Book Review of Second Karmapa: Karma Pakshi in The Review, IIAS.

Karma Pakshi Guru Yoga sadhana by Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche, published by Dharma E-books and free downloadable here:

Tibetan Language Sources

Karmapa 17, Ogyen Trinley Dorje.

–(2012). Karma Pakshi and a Jataka tale : A play with dance and a Tibetan opera – Tibetan Language Only.

–(2014). Teaching and empowerment of Karma Pakshi in Berlin, Germany.

–(2015). Teaching and empowerment of Karma Pakshi in the USA.

On the 2nd Karmapa 1978. Autobiographical Writings of the Second Karmapa Karma Pakshi and a work called Spyi Lan Ring mo — a defence of the Bka’ brgyud pa teachings addressed to G.yag sde Paṇ chen. Gangtok: Gonpo Tseten.

Second Zhamarpa, Khacho Wangpo, Five Great Deities of Samye Liberation-Story.

–Zhwa dmar 02 mkhaʼ spyod dbang po. “Karma pa chen poʼi rnam thar bsam yas lhaʼi rnga chen.” gSung ʼbum mkhaʼ spyod dbang po, vol. 2, Gonpo Tseten, 1978, pp. 23–110. Buddhist Digital Resource Center (BDRC), purl.bdrc.io/resource/MW23928_ABED4D.

–Zhwa dmar 02 mkhaʼ spyod dbang po. “Chos kyi rje dpal ldan karma pa chen poʼi rnam par thar pa bsam yas lhaʼi rnga chen (dbu me).” Bod kyi lo rgyus rnam thar phyogs bsgrigs(130), Par gzhi dang po, vol. 25, mTsho sngon mi rigs dpe skrun khang, 2010, pp. 11–86. Buddhist Digital Resource Center (BDRC), purl.bdrc.io/resource/MW1KG10687_43EEA2.

–Zhwa dmar 02 mkhaʼ spyod dbang po, and Karma pa 02 karma pakshi. “dPal ldan karma pa chen poʼi rnam par thar pa bsam yas lhaʼi rnga chen.” Karma pa sku phreng rim byon gyi gsung ʼbum phyogs bsgrigs, vol. 3, dPal brtsegs bod yig dpe rnying zhib ʼjug khang, 2013, pp. 259–350. Buddhist Digital Resource Center (BDRC), purl.bdrc.io/resource/MW3PD1288_B9853B.

Tselpa Kunga Dorje’s Red Annals. Tshal pa kun dga’ rdo rje. Deb ther dmar po. Beijing: Mi rigs dpe skrun khang, 1981. BDRC W1KG5760.

ENDNOTES

[i] Another scholar, Sam Van Schaik also states that:

“Karma Pakshi is a towering figure in Tibetan Buddhism. The first widely recognized reincarnate lama, or tulku, who established the Karmapa lineage, he was a poet, a scholar, and an accomplished meditator. Karma Pakshi’s fascinating story, including his time in the Mongol empire established by Genghis (Chinggis) Khan, is told here with clarity, thoughtfulness, and generosity. Selections from his poetry, visions, and teachings are beautifully translated. This is truly essential reading for those interested in Tibetan Buddhist practice and history.”

[ii] For example, in the section on the Mani mantra (2022: 34-35), the Red Annals and Second Zhamarpa’s account are both cited as textual sources, but no page numbers given. Manson kindly provided these for me on request.

[iii] For more on Trungpa’s revelation of the sadhana, see hereL The Story of the Sadhana of Mahamudra – Shambhala Pubs: https://www.shambhala.com/story-sadhana-mahamudra/

[iv] For more on the Karma Pakshi guru yogas and his connection to the deity Gyalwa Gyamtso, see here:

[v] More on the Karma Pakshi himself does not give much detail about the meeting, other than stating in his autobiography that Pomdrakpa told him, “You are someone with karmic propensity, aren’t you? Since meeting you, many pure visions have occurred. More detail is given in accounts by the Third Karmapa, Rangjung Dorjé, probably written about a century after the event, that the meeting occurred at Shabom, close to Selko Monastery where Pomdrakpa had been practicing and experiencing tantric visions for the past sixteen years.17 According to this later account, at the time of their meeting Pomdrakpa appears to have been impressed by the youngster, asking him, “Young practitioner, where are you going?” Chödzin replied, “I come from Sato and am going to Ü,” which also could be read, perhaps fancifully, as a symbolic “I come from higher ground and go to the middle.” (2022: 12).

[vi] “Indeed, in later tangka portraits from the eighteenth century onward, his personal meditation deity (yidam) is painted in the sky behind him as red Jinasāgara (Gyelwa Gyatso) in tantric embrace. His visions are not always of the red version of the deity: at times he witnesses a white or blue or yellow Avalokiteśvara.” (2022:35)

[vii] The full song is:

“In a mandala of four immeasurables,

I, a yogin with paired aspiration and application,

The stallion of bodhicitta I ride throughout the world—that is a necessity.

In the mandala of fourfold e waṃ,

The yogin of the completed fourfold empowerments,

With a victory banner empowering maturing and liberating,

I lead the fortunate—that is a necessity.

All buddhas in all times

As miraculously compassionate Avalokiteśvara

With the six-lettered superb speech mantras

Act for the benefit of beings—that is a necessity

Nondual samsara and nirvana,

The identity of immaculate dharmakāya,

Ultimate mahāmudrā,

I will accomplish buddhahood—that is a necessity.

For those adorned with multiple fears,

I pacify all the poisons—What

is called the four types of activity

Will protect the teaching—that is a necessity.

This short melody of five necessities—

The universal yogin,

With oral advice for the fortunate.

Sang it below the eastern mountain.”

[viii] For a transcript and overview of the 17th Karmapa’s teaching on the life of the 5th Karmapa (in March 2021), see here: https://dakinitranslations.wordpress.com/2021/03/05/the-karmapa-who-said-no-to-power-5th-karmapas-refusal-to-take-control-of-tibet/

[ix] The 17th Karmapa further explained that: “However, at some point there was some confusion in connection with the Ru-Shen clan who practiced Confucianism, and did not really like Buddhism. They said you don’t need to recite OM MANI PADME HUM because he is a Dharma King so as soon as you think about him he will know. They claimed that the mantra OM MANI PADME HUM could not be translated into Chinese, and one should therefore recite AM BANI HUM instead, which translates as “I am flattering you”. They said sarcastically as it means that, you should recite that instead. There were some palace guards who recited the mantra day and night. Even Yongle criticized them for it, as they were not doing their job as guards.”

[x] Chinese text – ‘The Names, Images and Name Mantras of the Buddhas and Bodhisattvas‘

In the Chinese National Library’s collection, there is a text about the exchange between China and Tibet of Buddhist texts and printing techniques during the Ming period. It is called The Names, Images and Name Mantras of the Buddhas and Bodhisattvas. [ His Holiness showed a slide of the book which has been published using these texts]. Later, they published it in book form. The text is primarily written in Chinese; there are some sections that include four alphabets including Lentsa, which is the same as the script used by the Newaris in Nepal and in Tibetan, and Mongolian with Chinese. In the introductions and conclusions it is mainly Chinese. Among these three sections is an image of Dezhin Shegpa among them. It was printed in Beijing in 1431, the sixth year of the reign of Emperor Zhengde, by Dezhin Shegpa’s Chinese student Xiūjī shànzhu ?

The foreword to this text, is in Chinese and Tibetan, the Chinese has been mostly lost but the Tibetan is complete. It reads, “The Dharma King Karmapa or Precious King of Dharma has shared many of the Dharmas and scriptures that he had given. So, these are now printed in this book.” Many researchers say this is an important text and is a good source describing how Tibetan Buddhism spread to the East into the Chinese areas.

Dear Adele,

<

div dir=”ltr”>Thank you for this wonderful writing about Karmapa Karma Pakshi and all your gre

Welcome Kati! I think your comment here was not finished though…..some is missing 🙂

Dear Adele, the link to the melody on the email appears to be broken, or at least I cannot access it on any of my devices. However, I see that you’ve published the mantra in musical notation, so I can learn it that way. Thank you so much! Kati

The Youtube link for the mantra is here: https://youtu.be/9FgFxqyo4ho

Thank you very much for a detailed and inspiring review. I’ve just ordered Manson’s book. You are doing wonderful work! But alas, when I click the link for your recording of the mantra, I just get an “invalid URL” notification. (I’ve tried 3 times and even refreshed your page.) Hope it can be fixed! With gratitude, A Reader

On Sun, Dec 18, 2022 at 5:20 AM Dakini Translations and Publications

Hello Barbara! Thanks for your comments, happy to hear you ordered the book. I will be reading it again and again, and writing more on some of its contents in the future too.

The links in the website article itself should work. Please check them again. If not, the link is here: https://www.youtube.com/shorts/9FgFxqyo4ho. I am not a singer and did it alone at home without any professional recording or mixing equipment but I thought people might enjoy hearing it, who cannot read musical notation. Do let me know what you think 🙂

Thank you for this lovely post. The link to the mantra doesn’t work. Could you repost it please?

Best wishes – Cate

On Sun, Dec 18, 2022, 5:19 AM Dakini Translations and Publications

Hello Cate thanks for your comments, the correct link is in the website and FB post. Here it is though, in case you cannot find it: https://www.youtube.com/shorts/9FgFxqyo4ho. May you find it beneficial 🙂