“Sthūlanandā was not well turned out, did not practice good deportment, and had very dirty ripped robes [revealing] great breasts hanging down like gourds and large buttocks. She was arrogant, unseemly, frivolous, fractious, and garrulous in her speech. [The families] did not respect her and did not host her.”— Mahāsāṅghika-Lokottaravādin Bhikṣuṇī-vinaya

“We have to see her mostly through male, and often, disapproving, textual eyes” –Schopen (2014:114)

“The depiction of Thullanandā as having mastery over both Dhamma and Vinaya thus allows the persistence of her greed (and other bad qualities) to point toward a larger conclusion: In spite of the great benefit provided by the Buddha’s word, neither Dhamma nor Vinaya themselves finally embody the profound internal transformation he calls for. In the end, they are only external trappings. The Buddha provides human beings with precious resources that can lead one to the ultimate good—yet there is no guarantee that they will have their desired effect. In this sense, far more than just a “bad” and greedy nun, I would suggest that Thullanandā becomes an emblem of the limitations of Buddhavacana itself.” Ohnuma (2013: 27-28)

“Moreover, when Thullanandā defends Ānanda’s dignity against the insults of Mahākassapa,

she implicitly endorses a “pro-woman” and “pro-nun” stance. This stance is cast in a negative light, however, by Thullanandā’s status as a “bad nun.” Ohnuma (2013: 56)

“I don’t do anything in order to cause trouble. It just so happens that what I do naturally causes trouble. I’m proud to be a troublemaker.” – Sinead O’Connor

Introduction

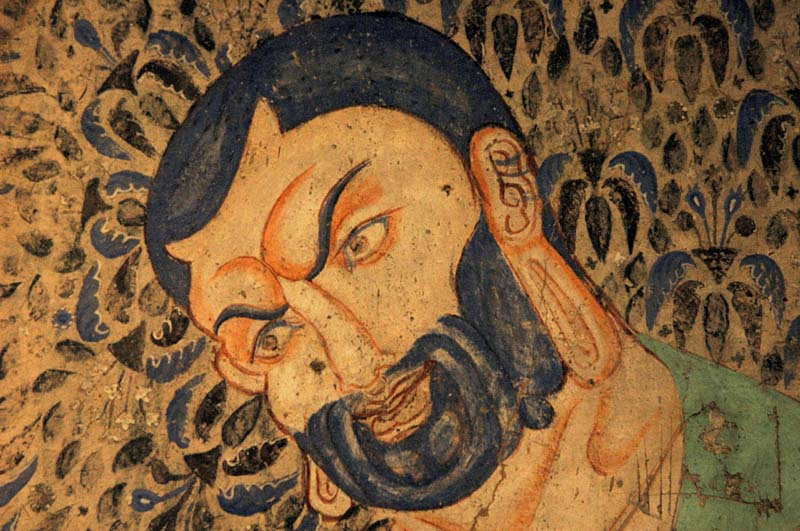

Today, for the new moon, I focus on the topic of the original Buddhist nuns, in particular the ‘trouble-maker’ nun, Sthūlanandā (Thullanandā (Pāli) and Bumgamo (Tibetan) (literally, “Fat and Joyful”).

She was one of the Shakyamuni Buddha’s nuns and sangha and had direct access to Buddha himself. According to Vinaya texts, she is reported to have enraged Buddha’s well-known male disciple called Mahākāśyapa (Osung Chenpo, འོད་སྲུང་ཆེན་པོ་). In fact, it was her showing disrespect to him that (it is said) caused Buddha to create extra rules for nuns regarding showing respect for the male monastics and was the catalyst for other rules (alleged to be created by Buddha) connected to her conduct.

Even though I have written about women alive at the Buddha’s time, such as his aunt, Mahāprajāpatī and Utpalavarṇā, I had never heard of Sthūlanandā the nun before, until the 17th Karmapa briefly spoke about in her in his current teachings (Day 3), and referred to here as one of the most troublesome nuns mentioned in the Vinaya texts of that time. I was fascinated by her alleged ‘bad behaviour’, or to put it more diplomatically (and fairly perhaps) her ‘audaciousness’. The 17th Karmapa himself asked why did she (and other nuns) so intensely dislike the Buddha’s student, Mahākāśyapa? One thing is clear that Mahākāśyapa was against another of Buddha’s well-known students, Ananda and his support for nuns and full ordination. The topic of Ananda and his role in the full ordination of nuns and his life, as well as Mahākāśyapa’s various criticisms of him at the First Council, is taken up in much more detail by the 17th Karmapa in Days 7, 8 and 9 of his teachings (more on that in a future post).

This essay briefly considers via contemporary research the creation of Vinaya rules via Sthūlanandā’s alleged role in it all. It aims to present some of the ideas and research in a general way that also draws attention to the topic of feisty or ‘difficult’ nuns documented at the time of the Buddha’s sangha community. Using work from more female-centred, fair representations of Sthūlanandā’s life and character by contemporary scholars, I outline and review work written about her, in particular the analyses by scholars such as Reiko Ohnuma and the Karma Kagyu nun and practitioner, Damcho Diana Finnegan and how and why Vinaya texts can be misleading about these women, their motivations and lives. I also briefly mention how at that time, nuns were seen by many as similar to prostitutes, in terms of their independence from the home, marriage, children and male control and domination and how Sthūlananda revealed that with her mocking actions.

I conclude, in line with Ohnuma, that Sthūlananda was a lot more than just a bad nun, and even if she was, she symbolises the futility of cleverly following and knowing the rules, yet internally not embodying the spirit and purpose behind them. Like monks who have virtual online sexual activities or meat-eating monastics, they find ways to explain why it does not breach Vinaya in its letter, completely oblivious to the actual spirit and purpose of those rules: inner transformation.

As Damcho Diana Finnegan states in her PhD thesis:

“This dissertation is dedicated to the female disciples of Buddha Śākyamuni whose stories await us in the Mūlasarvāstivāda Vinaya, including: Bhikṣuṇī Mahāprajāpatī Gautamī, Bhikṣuṇī Dharmadattā, Bhikṣuṇī Utpalavarṇā, Bhikṣuṇī Kṛśā Gautamī, Bhikṣuṇī Somā, Bhikṣuṇī Yaśodharā, Bhikṣuṇī Kacaṅgalā, Bhikṣuṇī Śailā, Bhikṣuṇī Kapilabhadrā, and, yes, Bhikṣuṇī Sthūlanandā, and the countless other nuns who have kept and are keeping the Buddhist monastic path joyfully open for women of the past, those of the present and all those many yet to come.”

It is in that spirit that I also dedicate this short article!

Music? For laughs, Fat-Bottomed Girls by Queen, and more seriously, Respect by Aretha Franklin and No Man’s Woman by Sinead O’Connor.

Adele Tomlin, 27th August 2022.

Texts and research on the lives of early Buddhist nuns and Sthūlanandā’s life

To consider Sthūlanandā’s conduct and character though, is not easy because as several contemporary Vinaya scholars have stated, the paucity of accurate material on Buddhist nuns and women at that time, and the fact that they were generally, if not all written by (and for) men means that these texts cannot be taken so literally as truth. More as historical literature of that time written by a certain gender and background.

As Peter Skilling writes in 2001, Eṣā agrā; Images of Nuns in (Mūla-)Sarvāstivādin Literature, we are now in a better position than before to study the lives of Buddhist nuns from literary sources but “these are mainly from the Theravadin and (Lokottaravadin-)Mahasaµghika traditions. What about the literature of the (Mula-)Sarvastivadins, another of the great Indian schools? Does it not have anything to tell us about nuns?…for the most part they have been ignored.”

Textual sources on Sthūlanandā come from Theravādin Pāli canonical and commentarial sources but also other Vinayas, such as the Mūlasarvāstivāda Vinaya, the one that the 17th Karmapa is using as his Vinaya source.

Sthūlanandā as represented in the Pali Vinaya

As I have detailed in the biography, there are several scholarly and academic articles on the subject of Buddhist nuns of original Buddhism (either Buddha’s students and sangha or not long after he passed away). One of the main scholars is Reiko Ohnuma, whose research is on the depiction of Sthūlanandā (Thullanandā) in Theravādin Pāli canonical and commentarial sources only (and is not exhaustive). In here 2013 article, Ohnuma states that:

“Thullanandā—in her Sanskrit form as Sthūlanandā—has a rich and complex life in the writings (especially the Vinayas) of various other schools. In fact, she is much more expansively featured in some of the other Vinayas—especially the Mūlasarvāstivāda Vinaya—than she is in the Theravādin sources. But since these depictions often depart, in one way or another, from the Pāli depiction of Thullanandā, and are worthy of separate, sustained study.”

She points out that the role played by Sthūlanandā in the Mūlasarvāstivāda Vinaya is also worthy of a detailed study. Ohnuma states that:

“there are some fragmentary discussions and representative episodes, see the following: Schopen (2007, 2008, 2009, 2010); Clarke; Finnegan. For example, both Schopen (2008) and Clarke have argued that Sthūlanandā in the Mūlasarvāstivāda Vinaya often serves as a comic figure and object of humor—and although there may be a hint of the same thing in Pāli sources, I do not think this is a prominent feature of the Pāli Thullanandā.”

Ohnuma asserts that Sthūlanandā is the most misbehaving nun in the Pāli Vinaya and that her ‘misbehavior’ is responsible for the promulgation of 2 Pārājika rules, 4 Saṅghādisesa rules, 7 Nissagiya-Pācittiya rules, and 24 Pācittiya rules. According to Ohnuma, these make up:

• = 12% of all rules incumbent upon nuns

• = 28% of all rules unique to nuns (not shared in common with monks)

However, Ohnuma encourages us to look past the words and numbers and see Sthūlanandā as representing something more complex and abstract:

“In Pāli literature, Thullanandā is well known for being a “bad nun”—a nun whose persistent bad behavior is directly responsible for the promulgation of more rules of the Bhikkhunī Pātimokkha than any other individually named nun. Yet these very same sources also describe Thullanandā in significantly more positive terms—as a highly learned nun, an excellent preacher, and one who enjoys significant support among the laity. In this article, I analyze the Pāli traditions surrounding Thullanandā. I argue that her portrayal is quite complex in nature and often extends beyond herself as an individual to suggest larger implications for the nature of monastic life and monastic discipline. In addition, once Thullanandā is labeled as a “bad nun,” she becomes a useful symbolic resource for giving voice to various issues that concerned the early sangha. In both ways, Thullanandā reveals herself to be far more than just a “bad nun.”

She states that there is no record of her attaining any level of spiritual progresss; in fact, she “fell away from the religious life” (Saṃyutta Nikāya) or she fell down dead and was reborn in hell (Mahāvastu) and is thus considered a bad nun in terms of both Dharma & Vinaya. Yet, she was also praised for her learned qualities:

“Before we dismiss Thullanandā as simply a “bad nun,” however, we should also note that these very same sources repeatedly describe her in a significantly more positive manner. Several times throughout the Bhikkhunī Vibhaṅga, for example, we are told that “the nun Thullanandā was very learned, she was an experienced preacher, and she was skilled at speaking of Dhamma”—all highly valued qualities in the Buddhist tradition and qualities not often attributed to nuns. According to the originstory for Nissaggiya 10, it was due to these very qualities that “many people attended to the nun Thullanandā” (Vin iv, 254). So skilled is she at speaking of Dhamma, in fact, that on two separate occasions, Thullanandā is even depicted preaching the Dhamma to King Pasenadi of Kosala himself, whereupon the king—“instructed, roused, excited, and gladdened with talk on Dhamma by the nun Thullanandā”—rewards her with expensive gifts (Vin iv, 255, 256). Moreover, Thullanandā’s success seems to extend well beyond her mastery of Dhamma to encompass the area of Vinaya or monastic discipline, as well: The origin-stories for various rules suggest that she has the seniority and requisite knowledge to act as a preceptor, ordain her own disciples, and settle legal questions within the Order—granted, in every such case, she does something wrong that leads to the promulgation of a rule, but her seniority and qualifications themselves do not seem to be questioned. In the origin-story for Saṅghādisesa 4, in fact, she displays her ample knowledge of the technical vocabulary of monastic discipline, criticizing certain other nuns for not knowing “what a formal act is, or the defect in a formal act, or the failure of a formal act, or the success of a formal act”—and contrasting this ignorance with her own expertise. In consonance with her mastery of both Dhamma and Vinaya, other passages make it clear that Thullanandā has her own pupils and followers,6 that she has no trouble receiving ample alms from householders, and that certain lay families are specifically dedicated to her support. This level of learning, seniority, preaching ability, and eminence in the eyes of the public is attributed to very few other nuns.” (2013:20-21).[1]

Ohnuma considers several examples of bad conduct cited as reasons why Buddha added rules to the Vinaya, such as her alleged selfish greed:

“Here, we can begin to see the advantages of depicting Thullanandā as a nun who is well-versed in the complex categories of monastic discipline: The obvious incongruity between Thullanandā’s mastery of monastic procedures, on the one hand, and the selfish greed that causes her to abuse them, on the other hand, effectively conveys the message that the outer forms and trappings of monastic discipline are meaningless unless one’s adherence to it is motivated by the proper mental disposition. External adherence to the rules is valuable only insofar as it reflects an internal state of mind. Thullanandā may follow the letter of the monastic law, but she constantly violates its spirit—and in order to highlight the distinction between the two, she must be depicted as having mastery over the former.”

“Mere knowledge of the Dhamma is useless unless the qualities it advocates are taken up and internalized. Thullanandā may be skilled at preaching on the dangers of greed, but without taking her own sermons to heart, she derives no benefit from her own knowledge. She preaches the Dhamma without internalizing it, and she masters the Vinaya without sharing its underlying motivation. In her case, mastery of the external trappings of both Dhamma and Vinaya is not undergirded by the genuine internal transformation that both Dhamma and Vinaya are meant to achieve. The depiction of Thullanandā as having mastery over both Dhamma and Vinaya thus allows the persistence of her greed (and other bad qualities) to point toward a larger conclusion: In spite of the great benefit provided by the Buddha’s word, neither Dhamma nor Vinaya themselves finally embody the profound internal transformation he calls for. In the end, they are only external trappings. The Buddha provides human beings with precious resources that can lead one to the ultimate good—yet there is no guarantee that they will have their desired effect. In this sense, far more than just a “bad” and greedy nun, I would suggest that Thullanandā becomes an emblem of the limitations of Buddhavacana itself.” (2013: 29).

“In addition to greed and favoritism, there are several other faults characteristic of Thullanandā, such as her tendency to make promises but fail to fulfill them, her inappropriate behavior with men (and encouragement of her followers to engage in the same), and her constant hankering after fame and public praise.” (2013:37)

But then she also considers Thullanandā as Proto-Feminist. In several stories, Thullanandā seems to get into trouble primarily for her insistence on defending the rights of women and refusing to show the proper deference toward powerful men. (Is this how she became the “bad nun”?) Examples of this are her favoritism for Ānanda, coupled with her dislike of Mahākassapa. “Ānanda stands for the pro-bhikkhunī faction, and Mahākassapa for his opponents.”[2]

Ohunama argues that:

“The ability of “bad” monks and nuns like Thullanandā to manipulate their detailed knowledge of monastic discipline in order to engage in unethical behavior—requiring the Buddha to promulgate one new rule after another, pertaining to evermore-specific situations—seems to be a common theme of Vinaya literature. I would suggest that perhaps this was a way for Vinaya authors not only to illustrate the cleverness of misbehaving monastics, but also to acknowledge the limitations of their own ethical system—its failure to finally capture, through a maze of specific rules, what it means to lead an ethical life. In this sense, one might argue that “bad” but Vinaya-savvy monastics such as Thullanandā serve a dual function: On the one hand, they illustrate individual faults and bad qualities, such as greed; on the other hand, they provide a critical commentary on the limitations of the Vinaya project itself—a subtle acknowledgment that no list of rules, no matter how comprehensive, can ever wholly crystallize the ethical life.”

Mūlasarvāstivāda Vinaya and stories about nuns

One of the earliest contemporary scholars and translators on original Buddhist nuns in the Mūlasarvāstivāda Vinaya literature is Prof. Peter Skilling. He writes in his 2001 essay:

“(Mula-)Sarvastivadin literature portrays nuns as teachers, some of whom played a significant role in the transmission of the Dharma. I have given only a few samples, collected at random, from a rich source, the avadana literature. There is a great deal more to be learned from this literature not only about the role of nuns, good, bad, and neutral, but also about the process of education and training within the community as a whole…. Several of the important stories, such as that of Soma, have no counterpart in the literature of the Theravadins of Sri Lanka.”

Another key scholar who has written about nuns according to the Mūlasarvāstivāda Vinaya tradition, is Damcho Dr. Diana Finnegan, a Karma Kagyu Buddhist nun and teacher and follower of the 17th Karmapa. Although Finnegan’s work is not only about Stulhananda, she includes her in the dedication of her PhD thesis (2009):

This dissertation is dedicated to the female disciples of Buddha Śākyamuni whose stories await us in the Mūlasarvāstivāda Vinaya, including: Bhikṣuṇī Mahāprajāpatī Gautamī, Bhikṣuṇī Dharmadattā, Bhikṣuṇī Utpalavarṇā, Bhikṣuṇī Kṛśā Gautamī, Bhikṣuṇī Somā, Bhikṣuṇī Yaśodharā, Bhikṣuṇī Kacaṅgalā, Bhikṣuṇī Śailā, Bhikṣuṇī Kapilabhadrā, and, yes, BhikṣuṇīSthūlanandā,and the countless other nuns who have kept and are keeping the Buddhist monastic pathjoyfully open for women of the past, those of the present and all those many yet to come.

In relation to Sthūlanandā, Finnegan states that:

“In a series of narratives that are scattered across the Bhikṣuṇīvibhaṅga but when placed together form a distinctive pattern, a nun—most often Sthūlanandā—is requested or herself undertakes to engage in certain activities that other nuns are then asked to perform. Those other nuns—nearly always Mahāprajāpatī Gautamī—balk and firmly state that they consider this inappropriate for them to do, and [the] Buddha then steps in to forbid any bhikṣuṇī from engaging in that behavior.” (2009:329)

Nuns seen as similar to prostitutes

Another interesting topic in which Finnegan mentions Sthūlanandā is how nuns were seen as similar to prostitutes in the Indian society at that time. She quotes fellow scholar Schopen:

“Buddhist sources themselves seem to suggest that it was an ongoing problem to mark and maintain a clear distinction between Buddhist nuns and prostitutes or loose women[3].

Finnegan states that :

”Besides housewife, we have also seen courtesan or prostitute presented as within the range of the role women may occupy in the MSV’s lay society. A full study of prostitution or courtesan culture as it appears in Buddhist texts of this period remains a desideratum.

The Brahmanic response to the challenge posed by the female ascetic is to depict her as a woman of dubious morals, associating with questionable people dwelling on the fringes outside respectable life— while the male ascetic has few such aspersions cast on his reputation. but it may suffice to say that prostitutes or courtesans are simply part of the social landscape in the Mūlasarvāstivāda Vinaya, and appear as figures in each of its 13 volumes.

With these two roles effectively carving out the entire terrain of where and how a woman might make her life in the society depicted in the Mūlasarvāstivāda Vinaya, we might expect a tendency to assume that if a woman was not serving in the home, she must be taking that other route….This view from the outside is echoed in the Mūlasarvāstivāda Vinaya as well.

Finnegan then explains that there are a number of slapstick accounts involving Sthūlanandā which are used as opportunities to clarify boundaries between monastics and prostitution. She relates one story:

“In a number of narratives, Sthūlanandā herself exploits the homology between the independent position of nuns and of prostitutes, at times crossing the boundaries between the two. In one such tale, Sthūlanandā decides to put on a wig, borrow clothes and jewelry from some musicians, and set herself up as a prostitute. A customer balks at her stated day rate—a whopping 500 kārṣāpaṇas—but is persuaded to come up with the money after she says, “Just take a look at this gorgeous body.” When at the last moment she herself has second thoughts, the man grabs her wig, outing her as a shavedheaded nun. After the altercation in which he insults her, Buddha establishes a rule forbidding the wearing of wigs.”

Finnegan adds that in the story the man calls Sthūlanandā a “bad baldie!” (mgo reg mo ngan pa) as soon as he grabs ahold and removes the hair/wig. Here, we see Buddha sticking closer to the particulars of the transgression in the formulation of the rule, as he often does. (2009:342-3)

The 17th Karmapa on Sthūlanandā and her intense dislike of Mahākāśyapa

Moving onto the 17th Karmapa and what he mentioned about Sthūlanandā recently, interestingly Finnegan mentions the important influence and role the 17th Karmapa had in producing her PhD work:

“My spiritual guide, His Holiness the 17th Gyalwang Karmapa, Orgyen Trinley Dorje, has been a centrally important presence in this dissertation. It was during a trip to see His Holiness that the narratives about women in the vinaya first suggested themselves as a dissertation topic. After learning of the topic, His Holiness strongly encouraged me to pursue the project, and himself read the nuns’ narratives, later retelling some of them in his public addresses to Tibetan nuns. His firm conviction that it was a valuable topic breathed the life into this dissertation that was a sustaining force through its completion. His presence continues after completion as well, when I return to Dharamsala to work on translations and engage in further research on bhikṣuṇīs. Though I may offer him all the respectful service of which I am capable, it is clear that this is always far exceeded by what I receive in turn. His Holiness’ immeasurable kindness and support for nuns illustrate the very best that can come of the asymmetrical relations of care that we see Buddha enjoining in the Mūlasarvāstivāda Vinaya.”

I agree with her and mentioned the positive influence of the 17th Karmapa had on my own work in the Introduction of all my three book publications. Thus, this glowing praise leads nicely on to the 17th Karmapa’s teaching (Day 3) based on the Tibetan Mūlasarvāstivāda Vinaya tradition, in which he related some stories about Sthūlanandā and her actions motivated by her dislike of Mahākāśyapa (Osung Chenpo, འོད་སྲུང་ཆེན་པོ་) that led to the Buddha making new rules:

“Once, while the Buddha was staying in Shravasti in a monastery donated by Anathapindada, Mahākāśyapa, who was one of the great disciples of the Buddha, right? He was staying at the older monastery of Deer Call in Shravasti. One morning, he put on his robes, took his alms bowl, and went to beg for alms in Shravasti. The bhikshuni Sthūlanandā (quite possibly the most ‘worst-behaved’ character in bhikshuni sangha) also got up in the morning, put on her robes, took her alms bowl, and went to beg for alms. She didn’t like Mahākāśyapa at all, I do not know why. When she saw Mahākāśyapa, she thought: “I’ll do something to make this idiot upset and unhappy.” She walked quickly and, arriving first at the house where Mahākāśyapa was going to beg for alms, she sneaked inside and hid behind the doorway. When he rang the bells on his staff to announce his presence, she said: “Noble one, there’s no food now. Go away.”

So Mahākāśyapa left and went to another house. Sthūlanandā continued to go ahead of him, hid inside and told him the same. She kept repeatedly doing this and telling him there was no food. After this had happened several times, Mahākāśyapa began to be suspicious. He was an arhat so he had clairvoyance. That means you have to do some samadhi meditation, and so he entered samadhi. and saw that this was Sthūlanandā’s doing. After seeing this, he said to her:

“Sister (the proper form of address to a bhikshuni by a bhikshu), it is not your fault. It is all venerable Ananda’s fault. He asked Buddha to ordain women. It is his fault that they became bhikshunis.”

This situation led the Buddha to make a rule that bhikshunis may not beg for alms at a home where bhikshus are going for alms. So basically, Mahākāśyapa was saying that this is not your fault, it is because Ananda allowed the nuns to take full ordination. He did not blame Sthūlanandā but blamed Ananda.

Another time, Sthūlanandā was teaching her followers dharma, she also had some students. When she saw Mahākāśyapa coming down the road, everyone else immediately got up out of respect, but Sthūlanandā did not lift her behind even a little bit. She just continued to sit there. Seeing this, her followers said to her: “Mahakashyapa is worthy of veneration by gods and humans. He’s such a great being. We all got up, but you did not budge from your seat. That is not good.” She said: “He’s not really a good Buddhist. He was a non-Buddhist who went forth and is the most idiotic of all the idiots. I went forth from the Shakya clan, I have memorised the Three Baskets of teaching, so why should I get up when I see him?” Buddha is said to have also heard about this event, and thus made the rule that bhikshunis must get up and stand, as soon as they see a bhikshu. If they do not get up, that is not alright.

There are many stories, these are just a few. So the final story I will mention is this one. Once, in Shravasti, Mahākāśyapa put on his robes and went begging for alms. It must have been summer as the rivers were full of water and Mahākāśyapa was unable to wade across the river by foot and had to cross by a bridge.

When he was crossing the bridge, Sthūlanandā saw him, again she thought ‘I will do something to make this fool upset and unhappy’ and rushed to the bridge and began swinging it (it would have been a rope bridge not like a solid bridge), causing Mahākāśyapa to fall into the water. Although he got entirely wet, his alms bowl sank and his staff was carried away by the river, he did not get angry but said:

“Oh Sister! All of this, the person who has made all these problems is Ananda! Ananda allowed women to go forth, take vows and be fully ordained and become foolish. This is why this incident happened. If Ananda had not let women go forth, this incident would never have happened. ”

When the Buddha heard about this incident, is is said he made a new rule again. That Bhikshunis are not allowed to cross a bridge at the same time as Bhikshus.

The Karmapa remarked that there are even worse stories than that one, such as when Sthūlanandā got Mahākāśyapa to fall in a cesspool full of excrement. However, he said:

“I do not understand why Sthūlanandā did not like him, but bhikshunis at the time must have looked down on Mahākāśyapa.

Following Buddha’s passing, during the First Council, Mahākāśyapa threw Ananda out of the assembly because he accused Ananda of making seven problems, one of which was advocating the ordination of bhikshunis which he alleged would decrease the continuance of the Buddha Dharma by 500 years.

This is why the Chinese master Yin Shun said that there are various debates and situations that arose between those two men. He thinks that the eight heavy dharmas were made at the request of the rigid, conservative traditionalist bhikshus.”

This is an interesting and important question. One of the most obvious reasons would be his dislike of the pro-Bhikshuni monk and brilliant student of Buddha, who was very popular with the nuns and helped them get full ordination. More on that in another post on the Day 6 and 7 teachings of the 17th Karmapa in which he explains some of the amazing qualities of Ananda and how he helped the nuns.

According to Indologist Oskar von Hinüber, Ānanda’s pro-bhikṣunī attitude may well be the reason why there was frequent dispute between Ānanda and Mahākāśyapa. Disputes that eventually led Mahākāśyapa to charge Ānanda with several offenses during the First Buddhist Council, and possibly caused two factions in the saṃgha to emerge, connected with these two disciples. More on that in another post (the 17th Karmapa is currently teaching Ananda and this issue).

In general, Mahākāśyapa was known for his aloofness and love of solitude. But as a teacher, he was a stern mentor who held himself and his fellow renunciates against high standards. He was considered worthy of reverence, but also a sharp critic who impressed upon others that respect to him was due. Compared to Ānanda, he was much colder and stricter, but also more impartial and detached, and Reiko Ohnuma argues that these broad differences in character explain the events between Mahākāśyapa and Ānanda better than the more specific idea of pro- and anti-bhikṣunī stances.

Sthūlanandā as proto-feminist and defender of Ananda and women’s rights

However, it is clear that Sthūlanandā does support Ananda and his pro-woman stance but dislikes the strict severity (and possible misogyny of Mahākāśyapa. Ohnuma (2013: 53-55) thus asks:

“Is there any evidence that Thullanandā shares Ānanda’s “pro-woman” stance or is committed to upholding the dignity of women and nuns? We already know that she is aggressive, independent, and utterly confident in her own capabilities. Could she also be seen as a sort of proto-feminist?

It seems to me that there are, in fact, several stories that are amenable to such a reading—stories in which Thullanandā gets into trouble primarily for her insistence on sticking up for the rights of women and refusing to show the proper deference toward powerful men. One such story is the origin-story attached to Saṅghādisesa 1. Here, a faithful Buddhist layman donates a shed to the Order of Nuns. After he dies, his son—who is not a follower of the Buddha—decides that the shed belongs to him, forcibly repossesses it, and orders the nuns to vacate. Thullanandā immediately objects: “No, Sir,” she says to the son, “don’t say that, [this shed] was given to the Order of Nuns by your father!” The dispute is brought before the ministers of justice, who seem uninterested in dealing with it. “Ladies,” they say to the nuns, “who knows whether or not [this shed] was given to the Order of Nuns?” Again, Thullanandā objects, reminding them of the legal transfer of the shed: “But, Sirs, didn’t you yourselves see, hear, and arrange witnesses for the gift of the shed?” The ministers of justice, realizing that “the lady has spoken truly,” award the shed to the nuns. The son becomes angry, reviling the nuns as “shavenheaded whores” (muṇḍā bandhakiniyo) rather than genuine recluses.

Thullanandā reports this abuse to the ministers of justice, which leads to the son being punished. Angered yet further, he then persuades a group of Ājīvaka ascetics to verbally harass the nuns; again, Thullanandā turns him in to the ministers of justice, and this time the son is locked up. This growing dispute soon leads to public criticism: “First, the nuns allowed this shed to be stolen away [from that son]; second, they had him punished; third, they had him locked up. Pretty soon, they will have him killed!” Eventually, the Buddha sets forth a rule prohibiting nuns from “speaking with envy” (ussayavādika) (Vin iv, 223-224).

Perhaps, then, Thullanandā’s fault in this case—even if she was morally in the right—was to go as far as filing a lawsuit against the son. This violates the basic idea that monastics— whether male or female—have renounced the ordinary world and thus removed themselves from the legal constructs that govern it; therefore, they should not be filing lawsuits against others, whether or not they have been legally wronged.

How, then, could this story be read as depicting Thullanandā as a proto-feminist? I believe that the gendered framework of this tale—pitting the nun Thullanandā, speaking on behalf of other nuns, against a wealthy male householder and some male legal officials—still carries some significance.”

Moreover, when Thullanandā defends Ānanda’s dignity against the insults of Mahākassapa,

she implicitly endorses a “pro-woman” and “pro-nun” stance. This stance is cast in a negative light, however, by Thullanandā’s status as a “bad nun.”

Physical and moral caricatures of women and the projection of male voices and standards onto women

It is also important to also consider how using Vinaya to view the world of the ancient Buddhist nun is an especially complicated project because as Amy Langenberg (2013) states:

“Many generations of feminist thinkers starting with Simone de Beauvoir have argued, representations of women are subject to gender norming, psychological projection, and mythos. Representational texts about women typically say more about the representer than the represented.”

As Langenberg recommends we can look at such texts as:

- literary products of a certain (gendered) worldview

- normative statements about ethical ideals

- records of custom

Langenberg (who seems to be more a compiler and commentator on other people’s translations, rather than a translator of the texts herself) points to an example of Sthūlanandā in a Vinaya passage subject to a gendered world-view about not only the ideal character of a woman, but also her physical appearance, from the Mahāsāṅghika-Lokottaravādin Bhikṣuṇī-vinaya:

“The Lord was staying at Śrāvastī. Sthūlanandā waylaid the nun Jetā who was on her way to Rājagṛha, saying, “You should stay here for the rains.” She praised her to [local lay] families: “Āryā Jetā is excellent and full of good qualities, bound [by discipline], and restrained. Give her respect.” [Jetā] approached those families, graceful when coming and going, observing, holding forth, wearing her monastic robes, and carrying her bowl. She was careful, upright, steady, polite, and economical in speech. Gracious, she was pleasing to both gods and men. They honored her, greeted her, rose to meet her, and offered her bowl, robes, and medicine for curing sickness. Sthūlanandā was not well turned out, did not practice good deportment, and had very dirty ripped robes [revealing] great breasts hanging down like gourds and large buttocks. She was arrogant, unseemly, frivolous, fractious, and garrulous in her speech. [The families] did not respect her and did not host her. She threw [Jetā] out, gesticulating and saying things. The nuns related this incident to Mahāprajāpatī, who told the Lord. The Lord caused Sthūlanandā to be summoned and questioned her. The Lord said, “You have done badly, [Sthūlanandā]. Whichever nun says to another nun, ‘You should stay here during the rainy season,’ and then later throws her out or causes her to be thrown out, has committed an offense requiring expiation.”

Langenberg writes that:

“As noted by several scholars, the nun Sthūlanandā (literally, “Fat and Happy”) is a stereotyped recurring character in the bhikṣunī-vinayas whose apparent function is to demonstrate uncouth, undisciplined behaviors so that they might be properly recognized and managed (Ohnuma 2013; Schopen 2008). Satirical stories of Sthūlanandā dramatize the female face of monastic undiscipline, including but not limited to problems with lay relations, disobedience, crassness, and sometimes, as here, the immoderate and aesthetically transgressive female body. Sthūlanandā’s characterization in our vinaya text as physically oversized and unattractive complies with aesthetic conventions governing the representation of the disgusting or ugly woman. In fact, neither the rule nor the contextualizing story absolutely requires any mention of Sthūlanandā’s pendulous, gourd-like breasts or large buttocks.

The essential points could have been made with reference to her behaviors alone; after all, nuns with more modestly sized breasts and buttocks are capable of poor hygiene, poor deportment, arrogance, crassness, garrulousness, and frivolity. The argument that a nun called Sthūlanandā really did have pendulous breasts and large buttocks is, pardon the pun, a thin one. As stock images of uncouth femininity, these outsized and ungainly physical features serve the representational project of this passage from the vinaya. In short, stories about Sthūlanandā, and other nuns, must be read critically and suspiciously with due attention paid to “the politics of representation.” Not only this, representational stories must be distinguished from and read comparatively with other texts from the bhikṣuṇī-vinaya literature that are not as subject to gender-representational interpolations.”

Here we can see how male views of the ideal female body and its association with morality and pure conduct pervade the Vinaya representations of nuns.

Double standards? Male ‘bad boy’ heroes but demonised ‘bad women’?

Also, as I wrote about here, if Drugpa Kunley and Gedun Chophel, who could easily be argued to have engaged in more derogatory conduct and speech towards women are celebrated, as is Vimalamitra, is not possible to re-evaluate even the so-called Vinaya texts on her condjuct as being an excessive response by conservative, patriarchal monks and not actually the Buddha’s words?

Conclusion – the futility of blindly following rules without embodying their spirit internally

To conclude, I return to Ohnuma’s assertion that perhaps what we can learn the most from Sthūlanandā’s ‘bad/bad-ass’ conduct is the futility and ‘silliness’ of rules if they are not accompanied with genuine, inner transformation.

Considering my own direct experience, one of the things that struck me the most in my own experience of ‘badly behaving’ monks, was their justifications for engaging in sexual activities, conversations, exchanging photos and videos online, in that it was ‘perfectly harmless’ because it did not breach their celibacy vow or the Vinaya. They were correct about that in a technical way if one looks at the Vinaya as merely being about a strict black and white set of rules and no flexible and adaptable to the current culture and its new inventions and technologies. However, monks continually watching online porn and engaging with online virtual sexual relations with women (nuns included) is surely not what Buddha had in mind when he created the rules about interactions with women, nuns and sexual relations in general, which were meant to reduce and prevent such contact and activities.

One could also say the same about the attitude of Tibetan Buddhist monastics to eating meat. I have witnessed (in predominantly vegetarian India) mainly Buddhist Tibetans and monastics actively going out and buying meat at slaughter-houses and shops and buying it in restaurants. They justify it by saying they did not kill the animal or misleadingly stating that Buddha permitted monastics to eat meat. Oblivious to, or deliberately disregarding the very limited and strict circumstances that Buddha ‘allowed’ it for Buddhists in India (begging for food only and only if the person offering it had not killed or bought the meat for that monastic – for more on that see recent teaching by 17th Karmapa here).

Also, fast forward 2500 years to now, and the mass factory farms where animals are uncompassionately specifically bred and slaughtered en masse without a care for the feelings of those animals, one can only imagine that the Buddha, if alive, would also have added to the Vinaya rules that such meat was also forbidden, and extremely harmful not only to the animals, but the environment and to people who worked in the slaughterhouses.

Thus, as Ohnuma says, Sthūlanandā is a symbol of the importance and superiority of inner transformation and the spirit of the Vinaya Rules, as opposed to being someone who cleverly knows and follows them to the letter, yet continually breaches their spirit and purpose on the inner and outer level. Sadly, we will never know why she and other fully ordained disliked Mahakasyapa so much, but the fact they did suggests there is something in his life-story that was never told by the women in it.

FURTHER SOURCES/READING

Finnegan, Diana Damchö. 2009. “For the Sake of Women, Too”: Ethics and Gender in the Narratives of the Mūlasarvāstivāda Vinaya.” PhD diss., University of Wisconsin–Madison.

Hirakawa, Akira. 1982. Monastic Discipline for the Buddhist Nuns: An English Translation of the Chinese Text of the Mahāsāṃghika-Bhikṣuṇī-Vinaya. Patna, India: Kashi Prasad Jayaswal Research Institute.

Langenberg, Amy Paris. 2013. “Mahāsāṅghika-Lokottaravādin Bhikṣuṇī Vinaya: The Intersection of Womanly Virtue and Buddhist Asceticism.” In Women in Early Indian Buddhism: Comparative Textual Studies, edited by Alice Collett, 80–96. New York: Oxford University Press.

Ohnuma, Reiko. 2006. “Debt to the Mother: A Neglected Aspect of the Founding of the Buddhist Nuns’ Order” Journal of the American Academy of Religion. 74.4: 861-901.

Ohnuma, Reiko. 2013. “Bad Nun: Thullanandā in Pāli Canonical and Commentarial Sources.” Journal of Buddhist Ethics 20:17–66.

Roth, Gustav, ed. 1970. Bhikṣuṇī-Vinaya Including Bhikṣuṇī-Prakīrṇaka and a Summary of the Bhikṣu-Prakīrṇaka of the Ārya-Mahāsāṃghika-lokottaravādin. Patna, India: K.P. Jayaswal Research Institute.

Schopen, Gregory.

―. 2008. “On Emptying Chamber Pots Without Looking and the Urban Location of Buddhist Nunneries in Early India Again.” Journal Asiatique 296 (2): 229–56.

―. 2009. “The Urban Buddhist Nun and a Protective Right for Children in Early North India.” In Pāsādikadānam: Festschrift für Bhikkhu Pasadika, edited by M. Straube, 359–80. Marburg, Germany: Indica et Tibetica Verlag.

―. 2010. “On Incompetent Monks and Able Urbane Nuns in a Buddhist Monastic Code.” Journal of Indian Philosophy 38:107–31.

―. 2014a. “On the Legal and Economic Activities of Buddhist Nuns: Two Examples from Early India.” In Buddhism and Law: An Introduction, edited by Rebecca Redwood French and Mark A. Nathan, 91–114. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

―. 2014b. “The Buddhist Nun as an Urban Landlord and a ‘Legal Person’ in Early India.” In Buddhist Nuns, Monks, and Other Worldly Matters: Recent Papers on Monastic Buddhism in India, 119–30. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.

Tomlin, Adele (2021) The power of a woman’s devotion: Utpalavarṇā, the first to greet Buddha’s Descent from the Heavens (Lhabab Duchen)

Tomlin, Adele (2021) RE-TELLING (AND RE-NAMING) ‘LHABAB DUCHEN’: WHEN MILK STREAMED FROM MOTHER’S BREASTS TO BUDDHA’S MOUTH AND BUDDHA’;S GREAT ACT OF REPAYING MOTHER’S KINDNESS

Tsomo, Karma Lekshe. 1996. Sisters in Solitude: Two Traditions of Buddhist Monastic Ethics for Women: A Comparative Analysis of the Chinese Dharmagupta and Tibetan Mūlasarvāstivāda Bhikṣuṇī Prātimokṣa Sūtras. (SUNY Series in Feminist Philosophy). Albany: State University of New York Press.

Tsomo, Karma Lekshe, ed. 2000. Innovative Buddhist Women: Swimming Against the Stream. Richmond: Curzon.

Tsomo, Karma Lekshe. 2004.”Is the Bhikṣuṇī Vinaya Sexist?” in Karma Lekshe Tsomo, ed. Buddhist Women and Social Justice: Ideals, Challenges,

Williams, Liz. 2000. “Whisper in the Silence: Nuns before Mahāpajāpatī?” Buddhist Studies Review 17.2: 167-173.

Willis, Jan. 1985. “Nuns and Benefactresses: The Role of Women in the Development of Buddhism,” in Y. Haddad and Ellison Banks Findly, eds. Women, Religion, and Social Change. Albany: State University of New York Press, pp. 59-85.

Wilson, Liz. 1995a. “Seeing Through the Gendered “I”: The Self-Scrutiny and Self-Disclosure of Nuns in Post-Aśokan Buddhist Hagiographic Literature.” Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion 11.1 (Spring): 41-80.

Wilson, Liz. 1995b. “The Female Body as a Source of Horror and Insight in Post-Aśokan Indian Buddhism,” in Jane Marie Law, ed. Religious Reflections on the Human Body. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, pp. 76-99.

Wilson, Liz. 1996. Charming Cadavers: Horrific Figurations of the Feminine in Indian Buddhist Hagiographic Literature. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Wilson, Liz. 2000. “The Body in Buddhist Traditions,” in William M. Johnston and Claire Renkin, eds. Encyclopedia of Monasticism. Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn, pp. 164-66.

Wilson, Liz. 2003. “Buddhist Views on Gender and Desire,” in David W. Machacek and Melissa

ENDNOTES

[1] “In fact, Thullanandā’s contradictory qualities have even led Talim to conclude that “one will not be wrong in presuming that there may have been two persons answering the same name,” since “one person could not be a bundle of such contradictory and altogether different characteristics” (53). Talim even goes so far as to divide Thullanandā’s offenses into two different lists, attributing one list of offenses to an intelligent yet crafty and cunning nun, and another list of offenses to a lazy, stupid, and fairly unimportant nun—with both nuns sharing the same name.9 I do not find Talim’s analysis to be convincing, nor do I think that our first recourse should be to posit more than one “Thullanandā.” (2013:22).

[2] Ohnuma cites the example of the Origin-Story for Saṅghādisesa 1

“A faithful Buddhist layman donates a shed to the Order of Nuns. After he dies, his son—who is not a follower of the Buddha—decides that the shed belongs to him, forcibly repossesses it, and orders the nuns to vacate. Thullanandā immediately objects: “No, Sir, don’t say that; this shed was given to the Order of Nuns by your father.” The dispute is brought before the (male) ministers of justice, who seem uninterested in dealing with it: “Ladies, who knows whether or not this shed was given to the Order of Nuns?” Again, Thullanandā objects, reminding the ministers of the legal transfer of the shed: “But didn’t you yourselves see, hear, and arrange witnesses for the gift of the shed?” The ministers of justice, realizing that “the lady has spoken truly,” award the shed to the nuns. The son becomes angry and reviles the nuns, calling them “shaven-headed whores.” Thullanandā reports this abuse to the ministers of justice, which leads to the son being punished. Angered yet further, he then persuades a group of (male) non-Buddhist ascetics to verbally harass the nuns; again, Thullanandā turns him in to the ministers of justice, and this time, the son is locked up. “Men” become critical of the nuns:

“First, the nuns allowed this shed to be stolen away from that son; second, they had him punished; third, they had him locked up. Pretty soon, they will have him killed!” In response to this criticism, the Buddha promulgates Saṅghādisesa 4: “If a nun speaks with envy about a householder, a householder’s son, a slave, a servant, or even a recluse who has gone forth (all male-gendered nouns), this nun has become guilty of an offense.”

[3] For his part, Gregory Schopen further suggests that an injunction against standing at the door of their residence should be read in light of other texts in which standing at the entrance to their building is depicted as something prostitutes do.

Adele-la, to begin ..

I’ll bet Sthūlanandā’s robes were worn and tattered because she was assaulted by those following Mahākāśyapa and his ego which poisoned those he had contact with. I even venture to assume Mahākāśyapa was the main assailant in that story and since it is relayed not by Sthūlanandā herself, my assumption is as valid as the writing itself. Mahākāśyapa’s conduct is not what the Shakyamuni Buddha taught, so why is it broadly accepted by so many of that time [and even to this day] that disgusting conduct from a male against a female is acceptable, sustainable, and even encouraged? Sadly, I see these extra rules for nuns given by Shakyamuni Buddha as a way to protect them from men like Mahākāśyapa, and the extra expectations were then used against nuns/females in a power grab.

On the other hand, I have a growing concern about Shakyamuni Buddha taking Mahākāśyapa’s side rather than Sthūlanandā’s when it came to her “troublesome” conduct. More abhorrent conduct by Drupka Kunley, the Mad Yogi, was accepted and even laughed off! There is no other reason for his acceptance and not hers other than to conclude that disgusting conduct from a male against a female is brushed aside and flippantly ignored, encouraged, and used as a reason to put sanctions on females; there is no other answer or reason for Sthūlanandā to be shunned and ridiculed [to this day] other than the fact that she outshined the monks following Shakyamuni Buddha and their egos could not handle her clear light. I have great pause too when it comes to considering the thought process of Shakyamuni Buddha and why he allowed this kind of abuse by those in his sangha.

Sthūlanandā should have been seen as Vajrayogini Herself [as well as all the other nuns in Shakyamuni Buddha’s entourage], and there are numerous stories of men shunning and ridiculing a worldly dakini emanation of Vajrayogini in the form of a prostitute or dirty beggar womxn only for this male to realize “he lost out” because of his own shitty ego. And so, if these stories are there as examples to us all – especially men – shouldn’t they be seen as a warning to a Vajrayana/Tantric practitioners to NOT be an asshole to females? Honestly, I can only conclude that most of these stories are for males because we females do not need to read over and over the disparaging journeys males have had only to realize the error of their ways. What we all should be reading is not about the cultural bullshit, but about these nuns’ lives and how they too are great masters in their own right.

I don’t believe Sthūlanandā was a troublemaker either and you have brilliantly shown what a story written by a womxn is, Adele! See, had you discriminated against the male characters of this story arch I would be so disappointed, but you have always written fairly BECAUSE THERE IS NO OTHER WAY OUR VOWS TELL US TO CONDUCT OURSELVES. And as for “[falling] away from the religious life” and dropping dead to *only be reborn in a hell realm* .. that says to me Sthūlanandā did what the praised Sakya Jetsumas did [the 3rd one, I believe)], when [she] had had enough of the ridicule and retreated to her own cave literally throwing her middle fingers in the air. Why can one set of womxn do the same as another and yet, there are different standards for each? Men simply need to step off the scales and stay in their lane. And hey, *being reborn in a hell realm* sounds to me like Sthūlanandā fulfilled her Bodhisattva Vows by being reborn where she was most needed and in the Vajrayogini fashion, she didn’t find a regular death to get there. Sthūlanandā simply possessed the qualities that her counterparts were envious of and the human condition, if not bridled, will undermine what it views to be its enemy. Comically, if nuns were seen as prostitutes and then “acted inappropriately”, I guess there’s no winning here at all! Truly, we are terrifying creatures – especially when we wear a wig!

As a side note, even Jesus (who I consider to be a Bodhisattva and not the leader of cultist “Christianity”) corrected men when they were being disrespectful to a womxn. I was raised Christian and it is blatantly apparent in the Bible (ugh, I loathe capitalizing that word) that Jesus used his influence to help womxn when men had abused them [think of the story of when the group of Rabbis brought a prostitute to Jesus showing him her nakedness and at that point, Jesus takes her and bows down to her drawing a line in the dirt between them and the Rabbis. What we need to be asking in all these “historical” stories is the storyline behind that conclusion, i.g., why in the fuck was a womxn in the back of the Jewish temple with a group of Rabbis when womxn weren’t even allowed that far into the temple?! Allow me to illuminate for you that these Rabbis bought her services and then decided to parade her out into the open thus making the Rabbis feel better about the sexual assaults they inflicted on her due to her “status”]. Other examples in the Bible include any life changing message from Jesus’ for his followers first given, told to, and delivered by a womxn, i.g. the resurrection.

Anyway, in my humble opinion Sthūlanandā was Vajrayogini and I sincerely believe in Her divinity through her actions. And here it stands to be stated: WE ARE ALSO CONSIDERED TROUBLESOME WOMXN and I stand beside Sthūlanandā in her continued fight for equality.

Thanks Kate for your insight and support of this website and such research! Also for sharing other interesting stories about women from other religious traditions.

Yes, there are many ways to view Sthūlanandā from the Vajrayana, Mahayana and Hinayana perspectives. One thing is for sure, many of the Vinaya stories seem to be saying that following and knowing the rules in a clever way is no substitute for actually following them in spirit and internally and so on. As Jane Goodall famously said: “It actually doesn’t take much to be considered a difficult woman. That’s why there are so many of us.”

Hello Adele! I’ve just read your post about Sthulananda and I’ve read her story beforehand in Karma Lekshe Tsomo’s book and personally I love the part where she defended Ananda against Mahakasyapa as well as the part about the shed and many, many others. I’m all like “YASS QUEEN” and “STAN THIS WOMAN” and so on. I’m fascinated by those deemed as “troublemakers” by society because usually those are the ones who brought social change/revolution (in a positive way). And uh props to Ananda for his pro-bhikshuni stance as well.

Now that DJ/Kate mentioned about her “growing concern about Shakyamuni Buddha taking Mahakasyapa’s side rather than Sthulananda’s when it came to her ‘troublesome’ conduct” or her having “a great pause too when it comes to considering the thought process of Shakyamuni Buddha and why he allowed this kind of abuse by those in his sangha”, I am curious and concerned too. I mean I could just say, “Well, it’s easy. Perhaps Shakyamuni Buddha is not perfect and not infinitely wise and compassionate as the scriptures say.” But perhaps there may be an alternative explanation to this?

About Mahakasyapa and him possibly hurting Sthulananda as suggested by DJ/Kate, all I can say is, “Not cool, man. Not cool. And seriously, you are not as awesome as you think.” IIRC, His Holiness the Dalai Lama said in the “Library of Wisdom and Compassion” series that even if beings have divine qualities or are highly realized and all, they still have to act in accordance to worldly conventions (as for this one, please correct me if I’m wrong).

Anyways, bring out more of those female-centric Buddhist stories because the male ones are already getting too mainstream (and it’s getting boring with all this male-centric stuff). And I really hate those men who create those male-centric Buddhist narratives.

And that’s all I have to say. I deeply apologize for the extremely strong, violent and judgmental language near the end of my message and controversial claim and thank you for your attention. You rock, Adele! (And the same goes for every single female Buddhist practitioner out there, whether historical or modern)

Thank you Sofie for your passionate and supportive response! Yes, I totally agree with what you say about ‘troublemakers’ as instigators of change, especially when they are women. Such women are always labelled bad by those who want to preserve the male privileges and sexist status quo and yes it is frustrating to read all these male-centred narratives and accounts, so I will try me best to redress that imbalance whenever and wherever possible!

Regarding your ‘violent’ language, I do not condone any form of inciting physical violence or hate towards any living beings. Compassion and love are the only answer, even for those who do terrible things. So I deleted them from your comment here. Hope you understand.

Thanks again for your interest and support in the work and website!